|

| Hannibal Hamlin (1809-1891) |

Vice presidents rarely cut any swath, and few people know much about them unless they succeed to the Presidency. Because Lincoln had a different vice president for his second term (Andrew Johnson who became president on Lincoln’s death), his first VP, Hannibal Hamlin, has been all but forgotten.

Hamlin was only six months younger than Lincoln, born in Paris Hill, Maine, on August 27, 1809. He began practicing law in 1833 in Hampden, Maine, a little south of Bangor, and married the same year. Politically, he favored the Jacksonian Democrats. He served in the Maine State Legislature from 1836 to 1841. He became a member of the U. S. House of Representatives in 1842, which he held for two terms. He served in the Maine State Legislature again for about a year, then was elected to the U. S. Senate to fill a vacancy, and won re-election to that office in 1851. His term in the Senate coincided with Lincoln’s in the U. S. House of Representatives, although they didn’t meet at that time. Hamlin was elected governor to the State of Maine in 1856, but he resigned to remain in the Senate for another term.

By this time, his strong views on the abolition of slavery and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise led him to withdraw formally from the Democrat Party. He turned to the new Republican Party, which reflected his political views, and worked to build that party’s platform and support. After helping to run campaigns in 1860 to nominate Lincoln as the Republican Party’s presidential hopeful, he was chosen as Lincoln’s running mate, and served one term as Vice President. He left that office in 1865, and enlisted in the U. S. Army as a private for the duration of the war (only a few months). He held various private jobs until 1869, when he again became a U. S. Senator, serving until 1881. With President Garfield’s appointment, he served as Minister to Spain from 1881 to 1882. He died on the Fourth of July, 1891, in Bangor, Maine, not quite two months short of his 82nd birthday. (1) A statue of him stands in the Capitol Building in National Statuary Hall.

This short biography serves to illustrate the life of a man dedicated to public service, with many years of experience in a variety of political positions. By 1860, Hamlin had achieved national renown as a man of character and integrity, incorruptible, and strongly in favor of the abolition of slavery without being violently radical.

Hamlin’s reputation garnered the nomination for the Vice Presidency. He was a stronger abolitionist than Lincoln, but was not as radical as some of the Republicans, including William Seward, the party’s leader, whose abolition views were too strong for the palate of most and, in effect, cut him from the race.

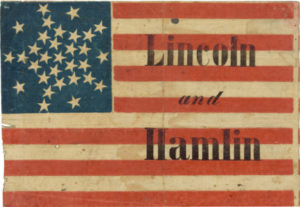

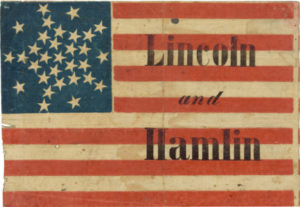

Campaign organizers had a field day with Lincoln’s and Hamlin’s names. The two men were obviously meant to be linked together: There was Hamlin, neatly inserted into “AbraHAM LINcoln.” This connection was used on campaign posters and banners across the country. (1)

The Republican convention results – Lincoln for President – did not please everyone in any of the four contending parties. In July of 1860, the Hon. James L. Orr of South Carolina stated that “Lincoln and Hamlin, the Black Republican nominees, will be elected in November next, and the South will then decide the great question whether they will submit to the domination of Black Republican rule – .” (7) (It’s interesting to note that four months before the elections, one Southern leader was quite sure of its results. Did the South wish to lose the election, to give them an excuse to secede? See my blog post about the secession chip that South Carolina had cultivated on its shoulder since the country’s inception – “The Tariff of Abominations, May 13, 1828”.)

|

1860 Political Campaign Cartoon: The united, Republican Lincoln-Hamlin train

bears down on the split Democrat Party, divided against itself. |

Lincoln and Hamlin never met until December of 1860. Lincoln wrote to Hamlin two days after the election, asking Hamlin to meet him in Chicago. There, in three days of very cordial meetings, they began the arduous and often delicate task of organizing an administration. (11) Lincoln was well aware that his Cabinet appointments could sway an entire state toward or away from secession, and he consulted with Hamlin and others extensively. Knowing he needed a New Englander in the Cabinet, he asked Hamlin to propose a few candidates. Lincoln was looking specifically for a New Englander to balance the Cabinet, “a man of Democratic antecedents.” (3, 5, 7) Of three reputable men whom Lincoln was considering – Amos Tuck of New Hampshire, Nathaniel Banks of Massachusetts, and Gideon Welles of Connecticut – Hamlin chose Welles, a Democrat whom Lincoln made his Secretary of the Navy.

Lincoln was not done with Hamlin yet. He sent Hamlin to New York State to woo Seward personally into accepting the position of Secretary of State in his Cabinet. Seward was still licking the wound of his loss to Lincoln, quite a blow to the noted leader of the Republican Party. Lincoln’s hesitation in asking for Seward’s acceptance of the post, which raised public speculation by the opposition press that Lincoln didn’t really want Seward at all, exacerbated Seward’s feeling of rejection, but Lincoln’s kind letters, one a formal request and the other a personal one expressing friendship and explaining why he took so long to ask, mollified Seward. He finally accepted, to the long-term benefit of both men and of the country.

Lincoln was not done with Hamlin yet. He sent Hamlin to New York State to woo Seward personally into accepting the position of Secretary of State in his Cabinet. Seward was still licking the wound of his loss to Lincoln, quite a blow to the noted leader of the Republican Party. Lincoln’s hesitation in asking for Seward’s acceptance of the post, which raised public speculation by the opposition press that Lincoln didn’t really want Seward at all, exacerbated Seward’s feeling of rejection, but Lincoln’s kind letters, one a formal request and the other a personal one expressing friendship and explaining why he took so long to ask, mollified Seward. He finally accepted, to the long-term benefit of both men and of the country.By the end of March, 1861, the Cabinet appointments were nearly complete. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune who favored Lincoln, could not contain his delight at the selections: “Yes, we did, by desperate fighting, succeed in getting five honest and noble men into the Cabinet – by a fight that you never saw equaled in intensity and duration … by the determined courage and clearheaded sagacity of Old Abe himself, powerfully backed by Hamlin, who is a jewel.” (10)

Of course, secession of states began immediately after the November election. Only a month into the new administration, the South fired upon Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, and the war, so long speculated, was now a reality. Lincoln sent Hamlin to New York City to monitor troop recruitments and movements (7), and

“to aid the leading men … in formulating and executing plans to defend the Union. … By the time [Hamlin] got to New York, on April 23, the city of Washington was threatened by rioting secessionist mobs in Maryland. Hamlin set up headquarters … and talked with an endless line of people from all over the nation. When Washington was completely cut off from the rest of the country for a short while, Hamlin was, in effect, at the head of an emergency government.” (1)

Once controls had been effected on Maryland and troops arrived in Washington City for its defense and to build an army, Lincoln sent Hamlin back to Maine in May to help raise troops. Hamlin himself attended the recruiting camps. He found green troops with no muskets for drill, so he pulled apart a picket fence and issued the stakes to the men to use in learning their manual of arms. (1)

The Congress came back into session in July, and Hamlin returned to Washington.

Hamlin was accustomed to vigorous political activity, from his years as state legislator, state governor, U. S. Congressman, and U. S. Senator. He had been instrumental in the administration’s early days, standing firm in crisis. Now, even though the war was all-consuming, the administration’s day-to-day actions settled into a certain rhythm. The mundane tasks of a Vice President, however, traditionally limited at best, chafed Hamlin. He was capable of greater challenges.

He was not without credibility: Lincoln relied on him heavily for advice, especially in matters of emancipation and the use of Negro troops in the conduct of the war. Lincoln wanted him included in the councils of government, and invited him to attend Cabinet meetings. Hamlin did so early on, but his attendance gradually diminished. He felt that he was an “unofficial consulting member,” (1) that unofficial status stifling his wont to speak freely as an advisor in the meetings.

Hamlin began to work behind the lines, using his position to strengthen his political interests, quietly. So quietly that even those who frequented the White House regularly failed to notice his activity, and began to consider him a “non-entity.” (2) His presence in the administration was so quiet that one of Lincoln’s secretaries, William O. Stoddard, stated,

I do not now remember that I ever saw Vice President Hamlin at the White House, though he may have been there a few times for all that. It seems that a sort of etiquette has been established, in accordance with which it is not considered in good taste for the second officer of the Republic to meddle much with public business, and which, at all events, keeps him away from the Executive Mansion. It would be difficult to give a good reason why he should not be numbered among the “constitutional advisors” of the President; but the contrary custom seems to be pretty firmly established. (9)

But he worked on. No sooner had the First Battle of Bull Run been fought (and lost) in July 1861, than he was in Lincoln’s office with Senators Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, all three urging the President to make slavery the prime issue of the war. Sumner pushed for emancipation to allow recruitment of the Negroes into military service. Chandler believed in emancipation in anticipation of the chaos it would cause throughout the South. Although Lincoln listened carefully, as he always did, he declined the suggestions on the grounds that these actions were premature. (11)

Hamlin was not deterred. Lincoln was under pressure from several fronts to do something about the slavery issue, including Frederick Douglass. By June 1862, Lincoln was considering different options by which to effect an emancipation proclamation. He invited Hamlin to the Soldiers’ Home, about three miles from the Executive Mansion where the Lincolns spent the summer, to review an early draft of what was to become The Emancipation Proclamation. They secreted themselves behind the locked doors of the library, and Lincoln read the complex document to Hamlin. Lincoln was apprehensive of Hamlin’s criticism, knowing Hamlin’s vehemence on the subject, but knowing that though Hamlin’s criticism could be harsh, it would be clear, direct, and valuable. Hamlin listened, and responded simply, “There is no criticism to be made.” (4)

The Emancipation Proclamation, released in September 1862 after a much needed Union victory in the Battle of Antietam Creek, was very well received by many Northern leaders, and it was hailed by newspapers across the country. But the issuance of the Proclamation and the reality of what could be done were two different things. Several months passed, and to the Radical Republicans (an active and vocal faction of the Republican Party), Lincoln did not appear to be doing anything with the Proclamation, with the blacks, or with slavery in general. After all, Lincoln could make the proclamation freeing all slaves within those states and territories currently in rebellion, but who would enforce this freedom?

Lincoln’s continued resistance to black enlistment, for a variety of reasons, prompted these pro-abolitionists to approach Hamlin in early January 1863. They proposed to support him if he would run against Lincoln in the 1864 Presidential campaign. Even as frustrated as he was himself with Lincoln for not moving as fast as he would have liked on these issues, he refused them, saying, “I am loyal to Lincoln, and it is our duty now to lay aside our personal feelings and stand by the President.” (11) Lincoln’s stance was more moderate than his own, but Hamlin recognized all along that Lincoln, in running a country at war, was dealing with a larger picture than slavery alone, and had to move more judiciously than many political factions may have liked. As he said much later, “I was more radical than [Lincoln]. I was urging him; he was holding back … And he was the wiser probably, as events prove.” (1)

|

| (Tell me these men can’t fight -) |

|

Hamlin’s next move was to push for Negro enlistments. Later in January, his son Cyrus, an army officer, came to him with a list of eight or ten other officers who wanted to command black regiments. Hamlin took Cyrus and several of these officers to Lincoln’s office to illustrate to the President that the idea of the military use of Negroes was not universally denigrated among whites. Lincoln was impressed by the officers’ interest and belief in the ability of black soldiers, and partly as a result of Hamlin’s visit, he finally approved the recruitment of blacks for military service. (11) When he sent Hamlin to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to begin organizing recruitment, Stanton (also a staunch abolitionist who had promoted the Union recruitment of black soldiers) literally hugged Hamlin with joy upon learning of the White House’s endorsement. (5)

Hamlin also used his office to some degree to curry favors from the President, primarily in assigning associates to various posts, and in assigning government contracts for military supplies to New England businesses. Hamlin generally went directly to Lincoln with his requests, including those for military appointments. As a result, he irritated Stanton no end, through whom Hamlin should have worked. At Hamlin’s recommendation, Lincoln endorsed putting the Chicopee [Massachusetts] Works into operation to manufacture cannon. Hamlin also requested that Lincoln appoint a Maine man as consul general of Canada. (7)

For one who receives little or no mention in most histories of Lincoln’s presidency, whom Stoddard never saw in the White House and whom Noah Brooks (a newspaper correspondent and friend of Lincoln’s) deemed a non-entity, somehow Hamlin’s administrative presence by mid-war was beginning to wear. The reasons why he was “a jewel” in 1861 no longer applied; the country had changed. By the time of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in November 1863, when the whole Lincoln family came down with a mild form of smallpox called varioloid, it occurred to political movers and shakers that the President could die, although in reality he was far from it. (The administration had become almost immune to the regular onslaught of assassination threats they received in the mail, and they had for some time stopped considering these letters terribly threatening.) A general belief somehow grew into an urban myth, that if Lincoln died, Hamlin could not measure up to the task, or perhaps hungered too much for the office. (8) No one seemed to remember that Hamlin’s political experience was far greater than Lincoln’s. Stoddard in his journal seems to reflect the attitude of the day when he says: “[Hamlin] would be President if Mr. Lincoln should die, and there is no means by which you can form an opinion of his capacity as dictator.” (9) (This statement makes one wonder if Stoddard was a Union man; an interesting observation from one who hardly remembered Hamlin’s presence in the White House.)

When the Republican National Convention convened in Baltimore in early June 1864 (4), party leaders had several names to nominate for a new Vice President. They wanted to present a broader platform, and felt that Hamlin made the ticket favor abolitionism too singularly. They and others repeatedly asked Lincoln for his preference, if he wanted Hamlin to stay on or if he wanted to work with someone new, but Lincoln consistently demurred, refusing to influence the convention. If anything was clear, Lincoln wanted the convention to decide for itself. (11) He believed that the convention should represent the people in their choice. To this day, no one conclusively knows whom Lincoln preferred, and it may be that he favored each man for different but important qualities that they could bring to the office. He knew and liked each man.

Andrew Johnson of Tennessee was ultimately nominated, even by Hamlin’s Maine men, for the party felt that Johnson represented strong portions of rebel states which had remained loyal to the Union, eastern Tennessee being one of those regions. They also believed that Johnson’s Southern roots might do much to mend relations between North and South after the war ended, which was clearly in sight.

Lincoln, a shrewd judge of men, knew of Hamlin’s dissatisfaction with the Vice Presidency, which office Hamlin often referred to as “the fifth wheel of a coach.” (1) Although Hamlin wanted to remain, he now found himself outside most political circles. The position was not the pro-active role which he had come to relish as a state legislator, governor, U. S. Congressman, and Senator. Perhaps if Hamlin had been more up-front about wanting to keep the post, Lincoln might have gone to bat for him. But Hamlin didn’t, and Lincoln didn’t. But Hamlin was probably torn between the potential of the office and the dismal prospect of four more years of chafing at the bit (unaware, of course, of Lincoln’s coming demise). On March 4, 1865, Vice President Hamlin rode in the carriage on Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol and watched, somewhat disgruntled by the situation, as Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the new Vice President.

In an interesting side note that illustrates Hamlin’s personal integrity and staunch support of the Union, Hamlin answered the bugle’s call. Very early on in the war, he had enlisted as a private in Company A of Maine’s Coast Guards, a reserve force. In August 1864, the Coast Guards were mustered to improve their organization should they be called up. Although he could have requested exemption from service because of his position, Hamlin refused, and joined the ranks in Kittery, performing his duties as a rank private with the rest of the boys in blue. He was 56 years old, a graybeard by any military standard, but he didn’t see that as an excuse to shirk his duty. He served several weeks, through the completion of the unit’s military exercises, after which he went on the campaign trail, stumping for Lincoln and Johnson. (13)

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL RESOURCES

1. Harwood, Michael. “In The Shadow of Presidents: The American Vice-Presidency and Succession System.” Philadelphia, New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1966.

2. Brooks, Noah. “Lincoln Observed: The Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks.” Michael Burlingame, ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

3. Miers, Earl Schenck, ed. “Lincoln Day By Day: A Chronology.” Dayton. Ohio: Morningside, 1991.

4. Kunhardt, Phillip B., Jr., Phillip B. Kunhardt III, and Peter W. Kunhardt. “Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography.” New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

5.Hesseltine, William B. “Lincoln and the War Governors.” New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955.

6. Nicolay, John G., and John Hay. “Abraham Lincoln: A History.” New York: The Century Company, 1890.

7.Lincoln, Abraham. “The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.” Roy P. Basler, ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

8. Randall, J. G. “Lincoln The President: Midstream.” New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1953.

9. Stoddard, William O. “Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Reports of Lincoln’s Secretary.” Michael Burlingame, ed. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. (Stoddard’s edition printed in 1890.)

10. Nevins, Allan. “The Emergence of Lincoln, Vol. II.” New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950.

11. Donald, David Herbert. “Lincoln.” New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

12. Dorman, Michael. “The Second Man: The Changing Role of the Vice Presidency.” New York: Delacorte Press, 1968.

13. Hamlin, Charles Eugene. “The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin.” Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1899.

Lincoln was not done with Hamlin yet. He sent Hamlin to New York State to woo Seward personally into accepting the position of Secretary of State in his Cabinet. Seward was still licking the wound of his loss to Lincoln, quite a blow to the noted leader of the Republican Party. Lincoln’s hesitation in asking for Seward’s acceptance of the post, which raised public speculation by the opposition press that Lincoln didn’t really want Seward at all, exacerbated Seward’s feeling of rejection, but Lincoln’s kind letters, one a formal request and the other a personal one expressing friendship and explaining why he took so long to ask, mollified Seward. He finally accepted, to the long-term benefit of both men and of the country.

Lincoln was not done with Hamlin yet. He sent Hamlin to New York State to woo Seward personally into accepting the position of Secretary of State in his Cabinet. Seward was still licking the wound of his loss to Lincoln, quite a blow to the noted leader of the Republican Party. Lincoln’s hesitation in asking for Seward’s acceptance of the post, which raised public speculation by the opposition press that Lincoln didn’t really want Seward at all, exacerbated Seward’s feeling of rejection, but Lincoln’s kind letters, one a formal request and the other a personal one expressing friendship and explaining why he took so long to ask, mollified Seward. He finally accepted, to the long-term benefit of both men and of the country.