|

| Edward Baker Lincoln (1846-1850) |

On February 2, 1850, Abraham and Mary Lincoln stood in Hutchinson Cemetery in Springfield, IL, and bade farewell to the younger of their “dear codgers,” 3-year-old Eddy, who had died the day before after a 52-day struggle with an illness. As the small coffin sank into the wintery grave, the little family, reduced to three, sank into an equally wintery grief.

Because Eddy was so young when he died, not much is known of him. He was born on March 10, 1846, and named after Edward Dickinson Baker, a US senator and former law partner of Lincoln. (Baker was the only sitting senator to be killed in battle while serving as a Union officer.) Lincoln reported to a friend eight months after Eddy’s birth that the baby compared favorably to his big brother at the same age, but was “of a longer order” (taking after his lanky father) than Bobby, who was “short and low” (like his mother).

Eddy is reported to have been a sweet child, precocious and talkative. He wasn’t quite two when in late 1847 the family traveled, by train and steamboat, to Washington City for Lincoln to serve in the US House of Representatives. During Lincoln’s term, the toddler often referred to his father as having “gone tapila,” baby language which his parents took to mean “gone to the Capitol [Building].”

Mary discovered after a few months that life in a few rented rooms across from the Capitol was far from the ideal she had imagined. In Springfield, the status of the wife of a Congressman had powerful, unique standing; in Washington, she was just one more freshman Congressman’s wife among dozens. In the spring of 1848, she took the children, Robert (4) and Edward (2), to her family’s home in Lexington, KY. The Todd homestead proved to be an environment far more suited to active youngsters than Mrs. Spriggs’ cramped boarding house on Capitol Hill.

Eddy took after his father in his love for animals. Writing from Lexington to Lincoln in Washington, Mary relates in May 1848 that Bobby brought a kitten home (“your hobby,” she emphasizes to her husband) which delighted Eddy. The toddler fell upon the orphan feline with utmost tenderness, insisting that water be brought for it. He hand-fed the kitten with crumbs of bread. When his grandmother (who hated cats) spied the kitten, she had a servant throw it out immediately, deaf to Eddy’s shrieks of outrage.

The Lincolns lavished love and affection upon their children, disregarding discipline and indulging their passions. They called the boys their “blessed fellows” and “dear codgers.”

Eddy was not a robust child. He was prone to sickness. He fell ill in December 1848 while Mary and the children were still at her family’s home in Kentucky. Mary left Bobby behind and took Eddy home to Springfield to nurse him.

A year later in early December of 1849, Eddy came down again with a serious illness, marked by a high fever, brutal coughing fits, and overall exhaustion. It snuffed out his short life within fifty-two days. Although no one knows for sure, historians speculate that the illness was either diphtheria or pulmonary tuberculosis, also known as consumption. (One online Lincoln research site states that in 1850, consumption killed more Americans than any other disease).

Life after Eddy’s death was nearly unbearable for Mary Lincoln, who mourned throughout most of her third pregnancy. The December 1850 birth of their third son, William Wallace Lincoln, was one factor that helped pull Mary out of her slump. Another which helped her re-emerge into the world after the funeral was the regular attendance that the little family soon took up at Springfield’s First Presbyterian Church. The pastor, Dr. James Smith, had conducted Eddy’s funeral service. His ministry and wisdom provided Mary with the strength to look to the future. Lincoln benefited from Smith’s work as well, and a deep friendship developed between the Lincolns and Dr. Smith.

|

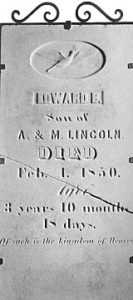

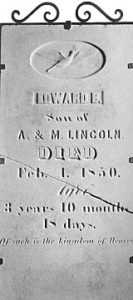

| Eddy’s original gravestone |

But the death deeply and permanently marked Mary. Her former bubbly nature succumbed to a hardening personality, and she refused to relinquish any shred of connection with her little boy. With the death of her mother when she was only six years old began a pattern which became tragically familiar over the course of her life. By the time she died in 1882, she had lost two more of her four sons and had seen her husband killed before her eyes. To assuage these strains, she delved further into spiritual matters, skirting the fringes of madness. By 1863, she engaged regularly in séances to contact her sons on the other side. She frightened her younger half-sister Emilie Helm with animated, intense, trance-like descriptions of dreams she had of Willie and Eddy coming in the company of her deceased half-brother Aleck to comfort her. Such tragedy in the life of a woman with an rock-bound core of emotional control would have shaken her foundation; in the life of one whose emotional stability was compromised from the start, it’s a wonder that Mary Lincoln did not go mad.

A few days after Eddy’s funeral, a four-stanza poem about his death appeared in the Illinois State Journal, author unnamed. The last line of the poem (“Of such is the kingdom of Heaven”) was etched on Eddy’s gravestone. Most historians guess that Mary or Abraham Lincoln penned the poem; perhaps they both worked on it.

Little Eddy lay in the Hutchinson Cemetery until 1865, when he was relocated to the Oak Ridge Cemetery to be with his father and his brother Willie whose bodies were brought from Washington after Lincoln’s assassination. In the Lincoln Tomb today rest Lincoln and Mary, with their three youngest sons – Eddy, Willie, and Tad (given name: Thomas). Oldest son Robert, the only son to live into adulthood, is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Eddy’s original gravestone is on display at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum in Springfield.

SOURCES

Lincoln, Abraham, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Roy P. Basler, editor, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 1955.

Turner, Justin G. and Linda Levitt Turner, Mary Todd Lincoln, Her Life and Letters, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, 1972.

Randall, Ruth Painter, Lincoln’s Sons, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, MA, 1955.

Emery, Tom, Eddie: Lincoln’s Forgotten Son, History in Print, Carlinville, Illinois, 2002.

Emerson, Jason, The Madness of Mary Lincoln, Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

Abraham Lincoln Research Site, Eddie Lincoln, by Roger J. Norton http://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln67.html