Tuesday, May 31, 2022

Memorial Day Musings

For sixteen years, I have participated in the Memorial Day ceremonies in the town of Millis, a small town in south-central Massachusetts. In 2006, Mark Slayton, a fellow Civil War reenactor and member of Millis’s American Legion Post 208, asked the small corps of fifers and drummers from his reenactment group to provide music for the parade. I played with this music company regularly.

After the American Legion breakfast, I went outside and pulled out the three fifes I had brought and tested each to see which one was playing the best that day. (Temperature and humidity affect how a woodwind instrument performs.) In a few moments, one of the veterans stood nearby and asked, “Who is playing the fife?” It was Charlie Grant, a WWII veteran who took up the fife in the 1960s. He was nearly blind, so he couldn’t see who was playing. We exchanged introductions and began swapping yarns about fife tunes, American Revolution history, and Bicentennial events.

Charlie and I became fast friends. Years before, he had put his fife in the attic, when caring for his ailing wife became more than a full-time occupation. After our meeting, he retrieved his fife, a Ferrari model highly regarded in the fife-and-drum world, and began playing at small local events for his friends and neighbors. I took him to fife-and-drum musters and he treated me to ice cream. He once said, “I never thought I’d ever play the fife again.”

Not long before Charlie died, he gave me his fife. By that time, he was living in a nursing facility. He no longer had the lung power to play it, and he was afraid that if he didn’t give it away when he was alive, it would get thrown out when he died. It is one of my treasures, not just because it is a valuable model no longer being made, but because it belonged to Charlie. He was a far more valuable model. At his funeral services I played some of his favorite tunes on his fife. No doubt he smiled from above.

Charlie died in 2012, and I visited him yesterday where his remains rest. I miss him still, even after 10 years, and I always will. But his friendship blessed me, and no one can take away those happy memories. We should all be so lucky

To Tease Your Mind

Death leaves a heartache no one can heal.

Love leaves a memory no one can steal.

Anonymous

(from an Irish headstone)

This image is evidence of frequent remembrance of a loved one. Jews have a tradition of placing a small stone on top of a headstone. It’s called a visiting stone. A lot of non-Jews have adopted this practice. It’s an appealing idea, isn’t it?

The Two-Pronged Nature of Grief

Remembrance and grief are walking hand-in-hand a lot these days, aren’t they?

Two weeks ago, my family gathered to celebrate my mother’s life, she who has been gone for a year and a half. It was a wonderful time to remember who she was and the legacy she left for us – her extended family (fairly large) and friends (who number in the thousands).

I am appreciating reconnecting with cousins I haven’t seen in over 40 years and making new connections with a number of relatives whom I have never met, and strengthening bonds with her friends, folks I know but never had the opportunity to get to know better. It will be great fun, and great consolation, to build and rebuild these relationships.

It pleases me to have posted above my desk a six-image collage of my mother – “Lorraine in the Diners.” She and her friend Sheryl took a road trip every spring, spending three or four days poking along back roads and remote locales in Maine and New Hampshire, just to see what was there. They hit every diner they came across. Sheryl took these photos of my mother contemplating menus and mile-high lemon-meringue pies. So, my mother beams at me (over that slab of pie!) every day.

Nine days later came Memorial Day, a national, annual day of remembrance specifically to honor our military service men and women who have made the ultimate sacrifice – their lives – that we may live with our God-given rights and freedoms, but which we as a people are obligated to maintain. As long as there are humans on the face of this earth, there will be some who would wrest those rights from us. We must maintain endless vigilance to keep them. As is often said, freedom is not free.

On Sunday, my husband and I visited the cemetery where three or four of his family’s generations are buried. Although most of them did not serve in the military, it’s fitting to use this holiday weekend to remember them, too. We hadn’t done this for several years – I don’t know why. I bought some marigolds and we planted them at each headstone. It felt good to do this, even though I never knew most of them. One is the grave of a little boy, the small flat stone engraved only with “Bobbie.” The cemetery office no doubt has the record of his last name, his age, the date of his death, but it is not evident to passersby. I wondered if the groundskeepers would be heartened to see a fresh flower at this weathered, lichened slab, to know that someone maintains his memory, even after seventy or eighty years.

Last week, I finished editing a memoir by a lady, whose description of how she dealt with grief after the death of her husband, from a rare form of cancer, is profoundly moving. She evinces almost a sense of joy – not necessarily happiness, which is a different thing – upon the arrival of the urn with his ashes at her home. She clutches the urn to her chest and rejoices – in a way – that “My Kenny is home!”

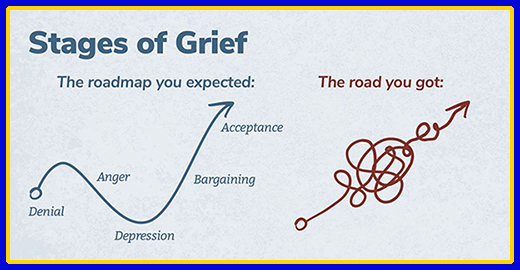

Some may view that as most peculiar. Although some may need counseling to overcome chronic grieving that they can’t get beyond on their own, there is no right or wrong in how one grieves, or for how long.

My friend Colleen sent me this thought right after my mother died: “Grief takes up all the space in your head.” I can’t think of a better way to describe that feeling when it’s so newly raw.

It seems fitting that, in the middle of all of these remembrance events, a blog post about the science of grief arrived in my inbox from Maria Popova, who produces “Brain Pickings,” also called “The Marginalian.” (Popova reviews books of all kinds, new and old. Her writings have prompted me to acquire several books.)

Here, Popova reviews Mary-Frances O’Connor’s latest book The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Love and Loss (2022). O’Connor is a PhD who has specialized in the study of grieving, both psychologically and physiologically. It’s not just in our heads.

Popova distills O’Connor’s material to explain that our brains encounter a paradox when a loved one dies. And it’s not limited to the dead: we grieve those whose bodies still live but whose cognition has succumbed to dementia or other mental afflictions. She writes:

“On the one hand, we lose people all the time — to death, to distance, to differences; from the brain’s point of view, these varieties of loss differ not by kind but only by degree, triggering the same neural circuitry, producing sorrow along a spectrum of intensity shaped by the level of closeness and the finality of the loss.

“On the other hand, no person we have loved is ever fully gone. When they die or vanish, they are physically no longer present, but their personhood permeates our synapses with memories and habits of mind, saturates an all-pervading atmosphere of feeling we don’t just carry with us all the time but live and breathe inside. Or the opposite happens, which is its own devastation — the physical body remains present, but the person we have known and loved, that safehouse of shared memories and trust, is gone — lost to mental illness, to addiction, to neurodegenerative disease.

“In both cases, the brain is tasked with the slow, painful work of reconstituting its map of the world, so that the world makes sense again without the beloved person in it. Mapping, in fact, is not a mere metaphor but what is actually going on in the brain, since our orientation in spacetime and our autonoeic consciousness — the capacity for mental self-representation — share a cortical region.” [In plain English, I think that means that our mental relationship with ourself and our mental relationship with others occupy the same part of our brains. (Is this plain English?) – SMC]

I really like that explanation above: Our loved one’s “personhood permeates our synapses with memories and habits of mind, saturates an all-pervading atmosphere of feeling we don’t just carry with us all the time but live and breathe inside.”

That is what enables us to smile and laugh at our memories of our loved one. That enjoyment eases the hurt of our loss. There is no reason to feel guilty about laughing and loving and finding happiness and joy once again.

The two-pronged remembrance idea of O’Connor’s has me thinking about our Memorial Day observances, and those of the Fourth of July and Veterans Day. As the keynote speaker pointed out at the event I attended yesterday, it is impossible for us to pay back those service men and women for what they have done for us – sacrificing for our sake their limbs, their health, or their minds, or ultimately, their lives.

(Let us not dismiss, either, those members of the military who have been fortunate enough to have served without undergoing physical or mental injury. They volunteered themselves to do what our country needed them to do. They were and are ready and willing to give that “last measure of devotion,” if and when called to do so. They are no less noble.)

None of them asks us to “make it up to them.” All they ask is that we do not forget what they have done, for our benefit.

Is that too big a thing to ask?

Let’s enjoy the family cookouts and the pomp and circumstance of the parades and other festivities. But let us be deliberate and intentional about remembering why we have set aside these holidays. They were not established for the sake of a day off from work or school.

Let us never allow indifference and neglect to erase the names of our deceased military from their tombstones. We never want to see this:

Let us never forget.

Sources

Images: Charlie Grant and the 13th Mass Infantry music company

photo by Sally M. Chetwynd

Image: “Lorraine in the Diners”

photos of Lorraine in the Diners by Sheryl Palmer

photo of collage by Sally M. Chetwynd

Image: Jewish gravestone

https://www.israelnationalnews.com/news/299756

Image: Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief

https://speakinggrief.org/get-better-at-grief/understanding-grief/no-step-by-step-process

Image: brain mapping

https://www.nature.com/collections/skwftbqxrh/

Image: POW-MIA Memorial Day float in Gray, Maine, 1991

https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/memorial-day-history#&gid=ci0283aa8020082458&pid=gettyimages-534703352

Image: unmarked headstone

https://www.israelnationalnews.com/news/267986