|

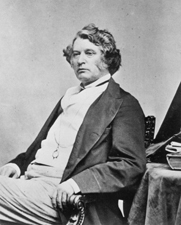

| Charles Sumner, 1865, by Matthew Brady |

Statesman Charles Sumner was one of the very few political men in Washington, DC, with whom First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln was friends. She believed that most of those who frequented her husband’s offices – office seekers, and men in Lincoln’s Cabinet, in the Congress, in the armies – were fortune hunters whose ambition exceeded their abilities. She was right about many of these, men and women alike.

Mrs. Lincoln – politically astute in her own right – saw in Charles Sumner, however, a kindred spirit, one of integrity and with the strength of character to stand up for what he believed in, more interested in the welfare of others than in that of himself – the kind of man she knew her own husband to be.

Sumner was born on January 6, 1811, in Boston, MA. He attended Boston Latin School, graduated from Harvard University in 1830 and from Harvard Law School in 1833, and was admitted to the bar in 1834. He first joined the Whig party, but became a founder of the Free Soil Party in 1848, a single-issue group that opposed the expansion of slavery into the Western territories. Sumner’s first election into the US Congress was as a Free-Soiler when he was elected to the Senate in 1851. The Free-Soilers became a faction of the new Republican Party which rose in 1854; Sumner was reelected as a Republican in 1857, 1863, and 1869, and served in the Senate for the rest of his life.

Sumner came by his abolition ideas quite naturally. His father, Charles Pinckney Sumner, was a Harvard-educated lawyer and abolitionist, who pointed out to his son that freeing the slaves was pointless unless they had equality within society. The elder Sumner shocked the proper Bostonians with his ideas of integrated schools and marriage between the races.

Between his father’s beliefs and the influence of William Ellery Channing, a Unitarian minister who had profound faith in the human potential through education, Sumner came to the conclusion that one’s environment played a critical role in one’s development. By creating a society where “knowledge, virtue and religion” took precedence, “the most forlorn shall grow into forms of unimagined strength and beauty.” (1)

For about three years, between ages 26 and 29, Sumner traveled in Europe, studying art, geology, Greek history, and criminal law, and becoming fluent in French, Spanish, German, and Italian. He took advantage of this time, too, to meet many leading statesmen in Europe. In France, too, he observed blacks mingling with whites in a variety of cultural and societal functions, with no hint that anyone took notice of the difference in color.

Upon his return to the States, he worked in a law office, but spent considerable time lecturing at Harvard Law School. His stature (6’-4”), self-possession, and presentation added to the impressiveness of his lofty themes on issues of the day, which were well researched and eloquently delivered. Soon, he found himself in increasing demand as an orator.

During these years, he began work in Massachusetts toward public education, education reform for blacks, prison reform, and against racial segregation. His successes were mixed, but his losses often influenced later legislation in favor of his interests.

Sumner became the voice of the anti-slavery forces in Massachusetts, and once he gained the US Senate, he specialized in foreign affairs. His views against slavery were so strong that in 1856, a vitriolic, 3-hour diatribe that he vented in the Senate, which ridiculed slaveowners as pimps (and, unfairly, made fun of the physical mannerisms of South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler, who had been severely affected by a stroke), provoked a violent attack by Butler’s nephew, Representative Preston Brooks, who beat Sumner nearly to death on the Senate floor. Suffering spinal and brain damage, Sumner was unable to resume his duties in the Senate for three years, returning to his seat shortly before the Civil War erupted.

His beliefs in the cultural, social, economic and political corruption which resulted from the existence of slavery had not diminished in the least during his convalescence. When friends suggested to him that he soften his stance, he replied, “When crime and criminals are thrust before us they are to be met by all the energies that God has given us by argument, scorn, sarcasm and denunciation.”

Sumner continued his fight for equal rights and suffrage for the black man. He was one of a regular group of abolitionists who pestered Lincoln steadily to end slavery, working with the president towards the emancipation policy that Lincoln eventually delivered. Throughout the Lincoln administration, Sumner often served as an advisor to the president, and was a frequent visitor to the Executive Mansion.

During Reconstruction, Sumner joined the Radical Republicans in Congress who wanted to punish the South harshly for having precipitated the war, believing that lenient and generous policies for the South showed weakness. This stance softened in the early 1870s, when he saw that conciliatory efforts would produce more useful results in knitting the Union back together.

Disagreement with President Ulysses Grant’s policies resulted in Sumner losing his committee chairmanships, and therefore his power base, in the Senate. Disgruntled, Sumner supported Liberal Republican Horace Greeley in his presidential bid in 1872. With Greeley’s loss, the last of Sumner’s diminishing power within the Republican Party evaporated.

Sumner never lost his zeal in promoting civil rights and suffrage for blacks. He co-authored the Civil Rights Act of 1875, introduced in the Senate in 1870 and enacted a year after his death. It took another 82 years before Congress passed any further civil rights legislation.

Nor did he neglect his belief in the benefits of education for blacks. In 1872, a school in Washington, DC, initially built in 1866 by the Freedmen’s Bureau (another pet project of Sumner) was rebuilt and rededicated as the Charles Sumner School, in honor of his advocacy. Renovated in 1986, it is now the official museum and archives for the DC public school system.

Charles Sumner died on March 11, 1874, at age 63, at his home in Washington, DC, of a heart attack. He lay in state in the US Capitol Rotunda (the first Senator to do so), before being sent home for burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA. Among his pallbearers were Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (age 67), Oliver Wendell Holmes (age 64), Ralph Waldo Emerson (age 70), and John Greenleaf Whittier (age 66), all Bay Staters with whom Sumner had discussed much philosophy over the years.

Sumner was by no means perfect. His strong opinions alienated many of his contemporaries. His lack of a sense of humor alienated his wife (a short and fruitless marriage of only 7 years, late in Sumner’s life). But he had the courage of his convictions, and no matter the cost to himself, did not hesitate to stand up for the rights of man.

SOURCES

(1) Donald, David Herbert. Charles Sumner and the Coming Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1960

(2) Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sumner

(3)Biographical Directory of the United States Congress http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=S001068

A few other books about Sumner and his times:

1. Sumner, Charles. The Works of Charles Sumner

2. Donald, David Herbert. Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970.

3. George Henry Haynes. Charles Sumner (G.W. Jacobs & Company, 1909)

4. David McCullough. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2011)

5. Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970)