Wednesday, September 2, 2020

Creative Alloys

My website designer, Mayur Gudka of Gudka Networks, cleverly prodded me to think deliberately about the text for each of my web pages. The more I thought about writing in particular, the more I realized that I want to kindle passion in others to write their stories, to connect their unique, discrete experiences – connections being alloys.

An alloy is a compound of two or more elements, usually metallic, melted together to produce a material with properties not found in each element singly – strength, corrosion resistance, durability, conductivity, hardness, malleability, and others.

A story is an alloy, too: a writer makes a connection between two unrelated objects or ideas, and the resulting alloy is a story that reveals the previously obscure relationship between them.

Right now, I’m researching material for a non-fiction book, the seed of which was planted over 50 years ago. I needed a connection to make the story relevant today. After letting the problem percolate on my back burner for six months, the connection revealed itself one morning in the shower. (Isn’t it funny how hot water ignites our brains?)

This is the stuff of originality. The nugget that triggers your interest and your research on that nugget are not original to you, but your creation from these elements becomes an alloy that is original. We all build from what came before, but the product is our own. Perhaps our work then serves as a nugget for someone else. It’s one facet of civilization.

Sally M. Chetwynd

Brass Castle Arts

Email Me | Visit Website | Sign Up For Newsletter

To Tease Your Mind

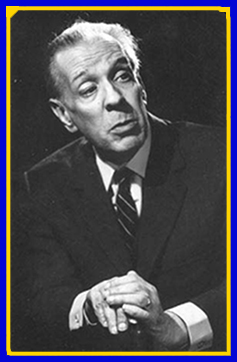

A writer — and, I believe, generally all persons — must think that

whatever happens to him or her is a resource. All things have been

given to us for a purpose, and an artist must feel this more

intensely. All that happens to us, including our humiliations,

our misfortunes, our embarrassments, all is given to us as raw

material, as clay, so that we may shape our art.

Jorge Luis Borges

August 24, 1899–June 14, 1986

Jorge Francisco Isidor Luis Borges Acevedo (how would you like to deliver that handle to the teacher on your first day of school?) was a short-story writer, essayist, poet, and translator from Argentina. The short stories in his published collections were interconnected by common themes (alloys, anyone?), and he is credited with launching the magic realism movement in 20th Century Latin American literature.

Borges is talking about alloys. We make them every day, blending that raw material – our experiences, direct and observed – into compounds never before combined. It’s the stuff of personal essays, memoirs, details that build flesh on the frame of fiction – of relationship.

This is why we can read and re-read a book that resonates with us and glean something new from it every time we do. Every day our perception of the world changes because of 1) the external influences on us – life experiences and relationships; 2) the internal influences on us – old cells discarded and new cells grown; and 3) the renewed analytical and creative connections – alloys – we generate from these influences, in an effort to understand what they mean to us, from the most basic needs – existence and survival – to higher thought processes – philosophy, theology, science, society, and culture.

We are not today who we were yesterday; we are not today who we will be tomorrow. Such change is incremental, but now and then we experience an epiphany, when elements connect in a meaningful new awareness or understanding.

Natterings & Noodlings

Some of you have asked about the significance of my business name “Brass Castle Arts.” Fair enough! Here’s the story.

I twiddled my thumbs about a website and its name for a long time. Some advised using my name for my domain. A lot of authors do this, which builds name recognition – like “sallychetwynd.com” or “sallychetwyndauthor.com.”

Nevertheless, I have taken a path broader than my name alone. Those who know me even slightly associate me with the name Brass Castle Arts, which I’ve used for ten years. My online presence offers more than published works.

The “brass” comes from two places: First, from a poem called “Brasswork” by a great-uncle, Fred Morong, a district machinist for the U.S. Light House Service. As a child, his chores included polishing the brass in the lighthouses his father kept. As an adult he heard the lament of the keepers, whose lighthouses he serviced, about the impossibility of keeping shiny the ubiquitous brass found everywhere at a lighthouse, from fixtures to fittings, from coal hod to buttons.

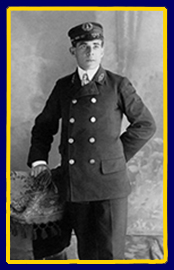

Here’s Uncle Fred, in his uniform, and his poem for the curious among you. Overalls – not shown here – were the working uniform for servicing a lighthouse. It was a greasy job.

BRASSWORK

or The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lament

Frederic W. Morong, Jr.

District Machinist, U.S. Light House Service

Oh, what is the bane of a lightkeeper’s life

That causes him worry, struggle and strife,

That makes him use cuss words and beat on his wife?

It’s Brasswork.

What makes him look ghastly, consumptive, and thin,

What robs him of health, of vigor and vim,

And causes despair and drives him to sin?

It’s Brasswork.

The devil himself could never invent,

A material causing more worldwide lament,

And in Uncle Sam’s service about ninety percent

Is Brasswork.

The lamp in the tower, reflector and shade,

The tools and accessories pass in parade.

As a matter of fact the whole outfit is made

Of Brasswork.

The oil containers I polish until

My poor back is broken, aching, and still,

Each gallon and quart, each pint and gill

Is Brasswork.

I lay down to slumber all weary and sore,

I walk in my sleep, I awake with a snore,

And I’m shining the knob on my bedchamber door.

That’s Brasswork.

From pillar to post rags and polish I tote.

I’m never without them, for you will please note

That even the buttons I wear on my coat

Are Brasswork.

The machinery, clockwork, and fog signal bell,

The coals hods, the dust pans, the pump in the well –

Now I’ll leave it to you, mates, if this isn’t – well –

Brasswork.

I dig, scrub and polish, and work with a might,

And just when I get it all shining and bright

In comes the fog like a thief in the night –

Good-bye, Brasswork.

I start the next day and when noontime draws near

A boatload of summer visitors appears

For no other reason than to smooch and besmear

My Brasswork.

So it goes all the summer, and along in the fall

Comes the district machinist to overhaul

And rub dirty, greasy paws all over all

My Brasswork.

And again in the spring, if perchance it may be

An efficiency star is awarded to me,

I open the package and what do I see?

More Brasswork.

Oh, why should the spirit of mortal be proud,

In the short span of life that he is allowed,

If all the lining in every dark cloud

Is Brasswork.

And when I have polished until I am cold,

And I’m taken aloft to the Heavenly fold,

Will my harp and my crown be made of pure gold?

No, Brasswork.

Second, I have portrayed a military engineer at Civil War reenactments for decades (an historical performance I offer on my website). This branch of the army, which became the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, has used the castle as a logo since its inception. The insignia worn on an engineer’s cap is a castle made of brass. (Yes, more polishing.) Brass and the brass castle have cast their stamp on me.

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Clock-makers, engineers, and professionals in other disciplines requiring fine instruments – commerce, industry, navigation, music, science, and military – have favored it for centuries because it does not create sparks, it doesn’t rust in damp environments, and it is easily tooled.

Sparks? What about sparks? Those who work with explosives use tools and implements made of brass because it won’t create a spark that could blow up one’s whole shebang – with a bang. As mentioned above, I re-enact at historical events. I play with the Northeast Topographical Engineers (mapmakers) and with Corbin’s Battery (artillerists). Some brass implements prevent sparks while we work with gunpowder, firing cannons. We land-survey and draft maps with other brass instruments like theodolites, Gunter’s chains, compasses, and ruling pens.

The percentage of zinc determines the hardness and malleability of brass – more zinc makes harder brass. The inclusion of small amounts of other elements like tin also determines the brightness and depth of its golden color. (Bronze is an alloy composed primarily of copper and tin.)

Brass may not rust, but it does tarnish, far more quickly than silver. Fog can reduce the shiniest brass to a dull brown overnight. Keeping a lighthouse was a full-time job, not the forty-hour-week most of us are familiar with. Full-time in the lighthouse service meant 24/7 responsibility, long before that term was coined. Polishing brass in a lighthouse occupied much of that duty. My own grandfather polished so much brass as a child at the Little River Lighthouse that he escaped inland as an adult and become a pharmacist. Chrome needs little if any polishing, no matter the weather.

Working on a tour boat one summer in the 1970s, I amused the tourists as I polished the brass on the boat, singing Uncle Fred’s song. Back in the 1970s, Gordon Bok (of Timberhead Music; drawing below), a folk music artist out of Camden, Maine, put the poem to music and taught the tune to me. Stephen Sanfilippo of the sea chantey group, From Away Down East, also has written music for the poem. He divides his time between Southold, NY, and Pembroke, Maine. (Neither man has yet recorded “Brasswork.”)

So I’ve produced a few alloys here, from websites and originality to lighthouses and poetry. There really is a connection among these, although perhaps tenuous in places.

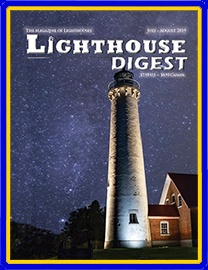

Lighthouse Digest Magazine

Lighthouse Digest Magazine

Lighthouse History Research Institute

Saving Lighthouse History Since 1992 – Working Today To Save Yesterday For Tomorrow

http://www.lighthousedigest.com/index.cfm

http://www.lighthousehistoryresearch.org/

For more than a quarter-century, Timothy Harrison, Editor, and Kathleen Finnegan, Managing Editor, have collected all-things-lighthouse – photos, official logs, journals and diaries, accessories, oral histories, restoration and preservation work, and everything in between – and shared their treasure with the world in Lighthouse Digest Magazine. The contributions from thousands around the world have helped Harrison and Finnegan to build a notable body of archives. Theirs is clearly a labor of love.

The lighthouse service began as a civilian enterprise, structured along military lines, as part of the US Dept. of Commerce. It was absorbed into the US Coast Guard in 1939. Today’s lighthouses are all automated, most of them with no personnel on site. Quite a number of lighthouses have been sold into private hands; some now serve as bed-&-breakfasts or other vacation lodging; many now belong to “Friends Of” organizations and are operated as museums. Many have been abandoned and lost to the elements. Funding to preserve and restore these historic structures is always a challenge.

Collecting and preserving the history of lighthouses is important because there are no more keepers to continue the tradition and no public institutions specifically assigned to preservation. Without the efforts of volunteers, much of our maritime heritage would be lost, not only about the structures but also about the men and women who kept them, the families who lived in them, and the organizations who provided them with traveling libraries, visiting pastors, holiday deliveries, rescue operations, and other services. There was no other occupation anything like that of keeping a lighthouse.

A Book Worth Checking Out

A Book Worth Checking Out

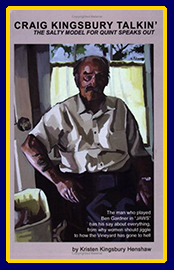

Craig Kingsbury Talkin’

Kristen Kingsbury Henshaw

Speaking of brass, in the sense of sass, Craig Kingsbury Talkin’ is a blend of memoir, autobiography, and oral history of Martha’s Vineyard. The author’s father is Craig Kingsbury, and she recorded his tales in the last few years of his life, while she served as his caretaker. Kristen, whom I met in February, and I swapped details about our books as we walked home from an event, and we agreed to swap books. She warned me about the salty language in hers, which she transcribed verbatim, but offered no apology for it. I wasn’t worried: I worked for four years in a shipyard, so I’ve heard it all.

I sent her an email a few days later:

“Oh, you evil woman! You pretended to warn me about your vile book but it was all a smoke screen for its real contents! What happens when I crack open the covers? Guffawing so loud that I can’t go to sleep! Tears of mirth flooding my face and soaking my pillow! Split ribs from laughing so hard!

“And I’m still in the introduction.

“I’ll send you the bill from my chiropractor, who will be hard put to re-align my funny-bone.

“No way am I returning the book to you. I need it as evidence. Evidence of what? I don’t know; I’ll figure out something. There must be a law somewhere against having so much fun.”

Besides the no-nonsense depiction of Kingsbury’s distinct, incorrigible, and unequalled independent personality, his oral history is invaluable. Who could remember the names of captains and crews of swordfish fleets out of Martha’s Vineyard’s numerous harbors, or the locations and owners of the multitude of cranberry bogs on the island, from eighty years before? Kingsbury did. Henshaw has captured his essence in his stories by allowing him to speak in his own, uncensored vernacular.

My favorite story is when Kingsbury was almost arrested for being drunk while driving his team of oxen. The fact that the oxen were doing most of the driving and hadn’t imbibed kept him out of the hoosegow (that time). Also, had the sheriff hauled him away, the deputy would have been stuck with driving the oxen home, and he had no clue how. It wouldn’t be fitting to leave the team standing indefinitely on the side of the road.

Word’s Worth

Oxford English Dictionary

brass Old English bræs; origin unknown, perhaps Old Swedish for fire,

to flame; dating from c.1000 AD

1. n. the general name for all alloys of copper with tin or zinc

2. n. generically, tools, implements, hardware, vessels made of brass

3. n. coins

4. n. impudence

5. n. a section of an orchestra or band

6. v. to coat with brass by electroplating

7. v. to burn, to scorch

Merriam-Webster.com

brass Old English bræs; Mid. Low German bras; before 12th C.

1. n. an alloy consisting of copper and zinc

2. n. the brass instrument section of an orchestra or band

3. n. bright metal fittings, utensils, ornaments

4. n. empty cartridge shells

5. n. brazen self-assurance; gall; sass

6. n. high-ranking government officials or military officers

Calendar & Announcements

Sunday, September 13, 2020, 1-3 pm

Merrimac Mic – a poetry-sharing forum

Isabell VanMerlin, host

merrimacmic@gmail.com

www.isabellvanmerlin.com

Isabell VanMerlin began Merrimac Mic several years ago as a forum to share poetry. It first met once a month on a weeknight at a coffee shop in Newburyport, Mass. Then it moved to the Merrimac Public Library in Merrimac, Mass., meeting on Sundays. Until the world opens up again, it meets via Zoom video-conferencing on the second Sunday of the month, from 1-3 pm. Visitors, guests, and regulars are welcome to read aloud a poem or two, or a short piece of prose, for everyone’s enjoyment. For an invitation to join the Zoom meeting, contact Isabell at merrimacmic@gmail.com.

She has collected the works of North Shore (Massachusetts) poets, those who have participated in Merrimac Mic, into five published anthologies. She has published other works, and is working to finish a memoir of her early life, Love and Garlic: The Deformative Years. (How can you go wrong with a title like that?)

She is also a big fan of haiku and other forms of poetry like it, such as tanka. She has been known to create haiku calendars, with a haiku in each day’s box. That’s a lot of haiku!

Isabell is upbeat, imaginative, enormously funny, and supportive of the creative arts in any form, but especially the written word. I love her sign-off: “All the best words!”

Sources & Credits

Mayur Gudka, Gudka Networks

http://www.gudkanetworks.com/

Jorge Luis Borges (content & image) – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Magic realism (not to be confused with science fantasy) – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_realism

Kenrick A. Claflin & Son, US Lighthouse Service Antiques

http://lighthouseantiques.net/Lighthouse%20Service.htm

Little River Lighthouse, Cutler, Maine

https://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=762

Frederic W. Morong, Jr., District Machinist, US Lighthouse Service

http://www.lhdigest.com/Digest/Photopage.cfm?Photo=1354

Gordon Bok, Timberhead Music

http://www.gordonbok.com/

Gordon Bok, pencil drawing

by Sally M. Chetwynd

Stephen Sanfilippo, From Away Down East

https://www.eastendbeacon.com/event/horton-point-lighthouse-events-tale-of-the-whale-opening-and-chanteys-with-stephen-sanfilippo/

Lighthouse Digest Magazine

http://www.lighthousedigest.com/index.cfm

Craig Kingsbury Talkin’

https://www.abebooks.com/9780976432296/Craig-Kingsbury-Talkin-Kristen-Henshaw-0976432293/plp?mc_cid=0235b575b6&mc_eid=[UNIQID]

Isabell VanMerlin

http://www.isabellvanmerlin.com/index.html