Saturday, September 19, 2020

Journeying to Exotic Lands

I read many books on totally different topics, and they are frequently long-since out-of-print volumes. (Two that I’m reading now date from 1925 and 1931.) It’s surprising how often books read within a few weeks of each other take me to the same locales around the world or otherwise relate to each other, making me think of unusual connections. (More alloys! See the September 2, 2020, newsletter.)

The most recent connections started in July with Giles Milton’s book, Nathaniel’s Nutmeg (1999), which told me about the Western/European competition to dominate the spice trade in Java and the tiny, remote Banda Islands in the 16th and 17th Centuries. The Dutch won out over Spain, Portugal, and England for the exclusive export of cloves, nutmeg, and pepper, and successfully established colonies for this trade throughout Indonesia.

Next I picked up Simon Winchester’s Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883, which took me right back to Java and Sumatra. In 1883, the catastrophic explosion of the volcano on the island of Krakatoa in the strait between Sumatra and Java blew both volcano and the island off the face of the earth, resulted in over 35,000 deaths, and affected worldwide conditions – commercial, maritime, meteorological, agricultural, and more – for years afterward. (I’m still in the middle of this book.)

Then a few days ago, a link received via a Facebook group was about a German named Oscar Speck, who paddled, solo, from Germany to Australia between 1932 to 1939 in a Faltboot, a folding kayak. His route skirted the coasts of Sumatra and Java. So here I was, gadding about Indonesia again, all within a few weeks. And all without a passport or frequent-flyer miles.

The Faltboot story resulted in an unexpected personal connection. A friend of mine once had one (and may still have). He and I worked at a regional planning commission in Maine back in the early 1980s, and he took me out in his boat one time. Quite an ingenious little craft.

Life truly is a spider’s web: pluck one strand and the whole thing shakes, sometimes a long time later.

Sally M. Chetwynd

Brass Castle Arts

Email Me | Visit Website | Sign Up For Newsletter

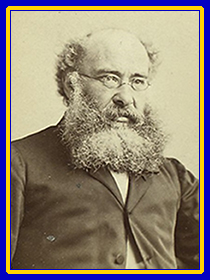

To Tease Your Mind

The habit of reading is the only one I know in which there is no alloy.

It lasts when all other pleasures fade. It will be there to support you

when all other resources are gone. It will be present to you

when the energies of your body have fallen away from you.

It will make your hours pleasant to you as long as you live.

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the Chronicles of Barsetshire, which revolves around the imaginary county of Barsetshire. He also wrote novels on political, social, and gender issues, and other topical matters.

How often have we promised ourselves that we’d read this book or that if we were laid up from an accident or surgery? Fortunately, most of us are rarely afflicted with such physical limitations, but it is nice to know that books are always there, no matter our circumstances.

My mother kept journals for about fifty years at our summer place on an offshore island in mid-coast Maine. She sold the house last winter to two of her granddaughters. As the girls have sorted through the house to accommodate their families with little children, they’ve brought these journals home to Mother, who will be 96 in a month. She derives great pleasure reading these now, which remind her of activities and events of those summer days.

What we read – published or unpublished, no matter when or at what age – should always bring us pleasure, even if the book is meaty, sometimes especially because it’s meaty, when we have to work – stretch our brain cells – to comprehend it. There is much joy in learning.

Natterings & Noodlings: Explosions

We’ve just passed the two-year anniversary of the natural-gas utility explosions that damaged so much of Lawrence, Andover, and North Andover in northeastern Massachusetts on September 13, 2018. The catastrophe killed one person, an 18-year-old high school senior, and injured over two dozen. About 30,000 had to evacuate their homes and businesses.

Although most residents of the Merrimack Valley were not directly involved, many of us in the eastern half of the state have friends and family who were severely affected. Some lost their homes entirely; others’ homes required major renovations. While waiting for the responsible utility companies to effect repairs and restore service, many either camped out in their homes for months without heat and electricity, some well into the winter months, or could not return until their homes were deemed habitable.

The gas in the Merrimack Valley was natural gas, not coal-generated like that produced in the city of Batavia (Jakarta, today), the capital of the island of Java in 1883. The gasworks there stored its gas in a telescopic tank called a gasometer. The daily pressure-reading records unexpectedly provided valuable data about the volcanic eruption on the island of Krakatoa, located in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra eighty miles west of Batavia.

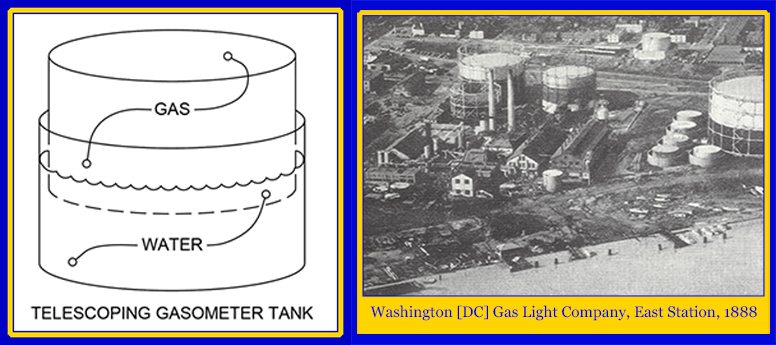

Gasometer is a misnomer, for it doesn’t measure gas; it is a tank that contains gas (also called a gas holder). The tank can be quite large, from 100 to 200 feet in diameter. One of the simplest designs is telescopic (see sketch below). Gas is pumped into the top tank, which floats on water in the bottom tank. The weight of the top tank pushes the gas with steady, reliable pressure to the utility’s customers.

The telescopic design was invented as early as 1824 in Britain. This method of gas production and distribution is rarely used today, but it was highly effective for municipalities and industries around the world for about a century and a half.

The telescopic design was invented as early as 1824 in Britain. This method of gas production and distribution is rarely used today, but it was highly effective for municipalities and industries around the world for about a century and a half.

What fascinates me is the gasometer’s ingenious simplicity. I first learned about gasometers in Washington Engineered by Vincent Lee-Thorp, a book about the civil engineering used to build Washington, DC. (The book attracted me because of its Civil War history and its Washington City history; I was once a licensed tour guide in our nation’s capital. I go gaga anyway over non-fiction about scientific discoveries, developments, inventions, and such. I’ll regale you about those at another time.)

In this scholarly treatise, Lee-Thorp covers everything from the early days of the city to the 20th Century, from spanning the Potomac with bridges, canals, and aqueducts to solving the Capitol Building’s chronic ventilation problem. About gasometers, he says:

“In 1860 a new West Station Plant was built [by the Washington

Gas Light Company] … on the site where the famous Watergate

Office and Apartment is today. The plant included a coal yard

on the Potomac and two massive gasometers, each consisting

of a circular steel tank, 100 feet in diameter, open on the top, into

which a similar tank, open on the bottom, neatly fit. The lower tank

was filled with water, which caused the upper tank to float, provided

it was filled with gas. The more gas in the upper tank, the higher

it floated. As the gas was sent out to customers via the pipelines,

the upper tank gradually sank down, but in so doing it kept a constant

pressure in the gas mains, and a constant pressure on the many gas

lights and customer use points.”

Back to the relationship of gas to the Merrimack Valley, Washington, DC, and far-away Batavia:

After three months of warning rumbles, vibrations, and emissions, the volcano on the island of Krakatoa launched into furious activity on Sunday, August 26, 1883. It spewed fire and rocks, ash and pumice that afternoon and evening, creating a tsunami that inundated most of the coastal towns and villages of the southeastern coast of Sumatra and the west coast of Java. Visibility was nil as darkness came long before sunset. Mariners in their ships were tossed about like twigs, caught between the dangers of the rain of rocks from the sky and the likelihood that the violent seas would smash them on the shores of the land masses close by.

Conditions were worse in the morning – the amount of ash in the air made it as dark as midnight and impossible to see one’s feet. At 10:02 am, the final explosion took place. Six cubic miles of ash, rock, dust, gases, and pumice were thrust up to thirty miles into the stratosphere; tidal waves over 100 feet high ravaged the nearby coasts, obliterating whole towns; atmospheric shock waves bounced back and forth across the face of the globe seven times, recorded in far-away England on meteorology hobbyists’ barometers; and the sound of the explosion was heard three thousand miles away.

Conditions were worse in the morning – the amount of ash in the air made it as dark as midnight and impossible to see one’s feet. At 10:02 am, the final explosion took place. Six cubic miles of ash, rock, dust, gases, and pumice were thrust up to thirty miles into the stratosphere; tidal waves over 100 feet high ravaged the nearby coasts, obliterating whole towns; atmospheric shock waves bounced back and forth across the face of the globe seven times, recorded in far-away England on meteorology hobbyists’ barometers; and the sound of the explosion was heard three thousand miles away.

It wiped out the island of Krakatoa. The northern and central cones, Perboewatan and Danan, 390 feet high and 1,480 feet high, respectively, were entirely gone, as well as a nearby island called Polish Hat. Rakata to the south, the highest cone at 2,690 feet, was sheared in half vertically. The hole left in the sea was a thousand feet deep.

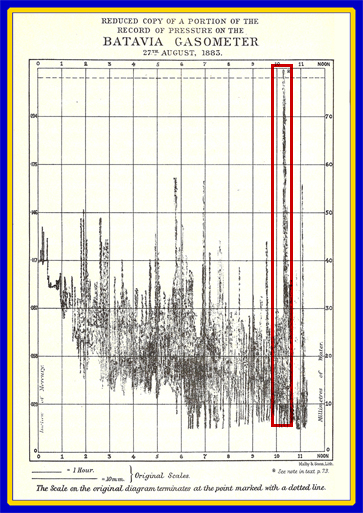

Not only did barometers and other measuring instruments record the eruption, but the gasometer in Batavia did, too. Overnight recordings of gas consumption (primarily for street lights) would show a gradual drop in pressure. Typically the gasometer’s instruments also recorded atmospheric pressure on its print-outs, tiny changes in the generally steady rise and fall of the stylus on the paper.

The paper recording of the fluctuations in gas pressure and barometric pressure at the Batavia gasworks on Monday, August 27, 1883, shows the violent fluctuation from the death throes of Krakatoa. The concussion sent the stylus off the paper, a pressure spike of over two and a half inches of mercury, an exponential extreme never observed before or since. (The red box on the Batavia pressure record below shows the spike, occurring a little after 10 am.)

So that’s the alloy I made today, a little romp along several branches of history. I hope you enjoyed the journey.

So that’s the alloy I made today, a little romp along several branches of history. I hope you enjoyed the journey.

A Book Worth Checking Out

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883

Simon Winchester (2005)

A British journalist and author of fourteen non-fiction books, Simon Winchester never fails to both entertain and educate, no matter the subject he explores. You may believe you have no particular interest in the subject of one of his books, but read just one, and it will never let you go. I’ve read with equal hunger two others of his, The Map That Changed The World and The Professor and The Madman.

In The Map That Changed The World, William Smith, an amateur, self-educated geologist in late 18th Century England, discovered in surveying coal deposits that he could distinguish different species of fossilized marine animals residing in different layers of coal. By tracing the angle of the layers, he could predict where they “daylighted,” that is, emerged at the surface for easy commercial access. He developed a complex map of southern England to show his discoveries. Smith catalogued distinct species in fossils forty years before Charles Darwin did so with live species.

In The Professor and The Madman, James Murray, a Scotsman, courageously tackled the impossibly massive task of creating an exhaustive encyclopedia that became the Oxford English Dictionary, THE definitive work of the English language. Murray received innumerable contributions from Dr. William Minor, an American Civil War veteran mentally disturbed by the trauma of the war, who was housed in an English asylum for the murder of an innocent man. The story was recently made into a film of the same name, starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn.

Now you know the gist of his book on Krakatoa, too. It’s just as good as the others. Check out any Winchester book if you’re short on reading material. You won’t be sorry.

Word’s Worth

Oxford English Dictionary

volcano from Vulcan (Latin) Roman god of fire, son of Jupiter and Juno

Italian; dating from 1598

- a conical hill or mountain composed of discharged matter, communicating with the interior of the globe by a funnel or crater, from which steam, gases, ashes, rocks, and streams of molten materials are ejected

- a state of things, liable to burst out violently

- a violent feeling or passion, esp. in a suppressed state

- (rare) to attack another violently

Merriam-Webster.com

volcano Italian or Spanish; ultimately from Latin Volcanus (Vulcan); dating from 1665

- a vent in the crust of the earth from which molten or hot rock and steam issue

- a hill or mountain composed of the ejected material

3. n. something of explosively violent potential

Conversations

Do you have comments or questions about this post? I’d love to hear them. Let’s talk!

Happy reading! Happy writing!

Sally

Sources & Credits

Image: Charles Krupa/Associated Press – WBUR News: “Looking Back At The Merrimack Valley Gas Explosions, 1 Year Later”

https://www.wbur.org/news/2019/09/13/merrimack-valley-gas-explosions-1-year-later

Image: Anthony Trollope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Trollope

Nathaniel’s Nutmeg by Giles Milton

https://www.amazon.com/Nathaniels-Nutmeg-Incredible-Adventures-Changed/dp/0140292608

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883 by Simon Winchester

https://www.amazon.com/Krakatoa-World-Exploded-August-1883/dp/0060838590

Gasometer – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_holder

Image: Washington Gas Light Company, East Station, 1888

Lee-Thorp, Vincent, Washington Engineered (2006)

Map of Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java: Google Maps

https://www.google.com/maps/

Image: Batavia Gasometer pressure register read-out, August 27, 1883

Winchester, Simon, Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883 (2003)

https://publicism.info/history/krakatoa/9.html