|

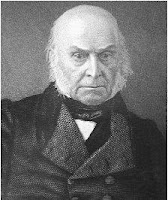

| John Quincy Adams |

The White House grounds which John Quincy Adams inherited upon his inauguration on March 4, 1825, were stark and chaotic. A budding botanist, John Q. determined to rectify the mess.

Eleven years earlier, President James Madison was driven out of the White House during the War of 1812 when British troops invaded the city and set fire to several federal buildings, including the President’s House. The damage to the structure was severe enough to prevent its occupancy for the rest of Madison’s presidency, which ended in 1817.

The White House’s next occupant, President James Monroe, put little work into the White House grounds. Aside from the insufficient funding, his own horticultural interests did not appear to extend beyond the requisite kitchen gardens. The financial Panic of 1819, two years into Monroe’s first term, eliminated any further funding for landscaping. Only necessary monies were dedicated to the residence itself.

Between 1814 and 1827, these underfunded efforts at landscaping and grounds-keeping in the Madison and Monroe administrations were insufficient to grace the building, even though both presidents were skilled in agriculture and horticulture. In addition, incomplete grading and drainage work which had dragged for years blemished the grounds when Adams moved in.

John Quincy Adams, on the other hand, who knew little about gardening when he entered the White House, made far more significant contributions to the White House grounds and to the national advancement of agriculture and horticulture than either of his two predecessors who were experienced in the world of flora.

John and Abigail Adams had quite deliberately raised young John Q. to be a statesman, and over his career, John Q. held nearly every political and diplomatic post in the United States, becoming well versed in history, literature, languages, and philosophy, with artistic forays into painting, sculpture, and music. In his earlier years, his public career was foremost, but in his later years, he broadened his horizons and interests into the sciences, especially botany. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution, and promoted the silviculture of utilitarian as well as ornamental trees.

John Quincy Adams discovered a delight in digging his hands into the earth. President or not, he thought nothing of ranging the woods still then in and around Washington City to collect acorns from the five species of oaks there, which he planted on the White House grounds. In hands-on botanical practice, John Q. found a renewal of the spirit which he no longer found in his public office, in his books, or in his marriage.

Adams looked to Thomas Jefferson’s original landscaping plans for inspiration, and in 1827, began to put Jefferson’s vision into effect. He hired John Ousley as White House gardener to put his ideas into effect; Ousley filled the bill more than adequately for Adams and several of the following presidents.

Besides his work with the White House grounds, Adams endeavored to launch the silk-worm industry, and to restore the Eastern forests, nearly gone by this time, which had supplied live-oak and white oak timber for ship-building since the settlement of the continent. He believed that these two industries could go far in furthering American industrial and commercial independence.

Being a relative neophyte to botanical interests, Adams befriended specialists and collected books and treatises from Great Britain and Europe about plants, gardening, botany, forestry, agriculture, and so forth. He studied these works constantly. The more he learned, the more questions he had. This he found frustrating, but fascinated with these subjects, he persevered, applying what he read to his own experiments and observations.

|

| White House south face & gardens – 1831 |

After much study, Adams began to put his ideas into practice. In April 1827, he and his steward Antoine planted two varieties of walnuts, hazelnuts, three varieties of chestnuts, and apple seeds on the White House grounds.

A few weeks later, he expanded upon his idea of an American museum of trees to include foreign trees, fruits, and herbaceous plants which would benefit and bring profit to American commerce and culture. He had the Secretary of the Treasury send to every U.S. consul around the world a circular announcing the president’s project to collect “forest trees useful as timber; grain of any description; fruit trees; vegetables for the table; esculent roots; and, in short, plants of whatever nature whether useful as food for man or the domestic animals, or for purposes connected with manufacturers or any of the useful arts … “ (1) This mirrored Jefferson’s earlier tactics to import plants and seeds valuable to the new American nation.

Within three months, American ship captains began to deliver seeds and saplings from all over the world. Soon, Adams had tiny forests growing in both Washington and at his house in Quincy, Mass.: Spanish chestnuts, cork oak, English oaks, buttonwoods, elms, tamarinds, pears, shag-bark walnuts, horse chestnuts, hickories, persimmons, tulip poplars, limes. By 1828, his White House efforts boasted over 700 saplings of 20 varieties.

In early June 1827, Adams wrote in his diary about his plantings at the White House, in the ground and in pots:

“In this small garden, of less than two acres, there are forest- and fruit-trees, shrubs, hedges, esculent vegetables, kitchen and medicinal herbs, hot-house plants, flowers, and weeds, to the amount, I conjecture, of at least one thousand. One-half of them perhaps are common weeds, most of which have none but the botanical name. I ask the name of every plant I see. Ousley, the gardener, knows almost all of them by their botanical names, but the numbers to be discriminated and recognized are baffling to the memory and confounding to the judgement. From the small patch where the medicinal herbs stand together I plucked this morning leaves of balm and hyssop, marjoram, mint, rue, sage, tansy, tarragon, and wormwood, one-half of which were known to me only by name – the tarragon not even by that.” (2)

Sadly, much of his horticultural work went for naught when Adams left office. Andrew Jackson entered the White House with a raucous and rowdy inaugural party which left not only the White House in a shambles but much of Adams’ work trampled. The damage extended well after the party was over. Adams, whose relationship to Jackson was unpleasant, to say the least, suspected that the destruction of his plantings may have been deliberate, a political message from Jackson supporters to eradicate Adams’ political legacy.

|

| JQA Elm Tree in 1965 |

Nevertheless, some of Adams’ horticultural legacy endured, including an elm which he planted as a seedling, which witnessed many administrations on the White House grounds until 1991, when it was taken down because of structural concerns. First Lady Barbara Bush planted a root cutting from this tree to replace it. (3)

Think what Adams might have accomplished in this field had he had the opportunity to cultivate his interests as a young man.

RESOURCES:

White House Landscapes: Horticultural Achievements of American Presidents by Barbara McEwan (New York: Walker and Company, 1992).

1. “Seeds of the Presidency” by Jack Shepherd, Horticulture, January 1983, p. 42.

2. Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, ed. by Charles Francis Adams, (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1875), 7:291.

3. Tree Speak: “Notable American Elms,” January 20, 2011 (also photo credit) http://blog.caseytrees.org/2011/01/notable-american-elms.html