Friday, September 10, 2021

Friday, September 10, 2021

Work: An End Unto Itself

As a species, we are designed for work. Without it, we wither physically, spiritually, mentally, and morally. A lack of work can literally kill us – a very slow death. Our culture, however, has trained us to consider work as – well – as work: chore, toil, labor, tedium, grind, travail, rat race, rut, hardship. We’re supposed to think of it only as a means to an end.

But work affirms our purpose on this earth. It’s an end unto itself. Work supports our health. It stretches more than our physical muscles; it also stretches our brains and increases our intelligence, as we solve problems and design new things. It keeps us young in many ways.

For some, the physical aspects of work intrigue us. I find mechanical things a great wonder. When I spend time at my family’s summer place, on an offshore island in mid-coast Maine, I love to tinker. Something always needs attention, particularly when opening up in the spring. The wooden toggle to lock the outhouse door from the inside has broken at its pivot. The lawn mower’s gas cap is AWOL, so a vented substitute needs to be carved from a wooden plug. Bittersweet has taken over the lilac bush, so a counter-attack is in order with garden pruners and herbicide. The key to the front door won’t turn in the lock, so the whole assembly needs to be removed, opened, and emptied of generations of dead flies that got stuck in there (crawling through the keyhole toward the light) and died, jam-packing it absolutely full.

My mother beseeched me every year, when we opened up, not to feel obligated to spend all my time there working, to take time to enjoy the place. But every year I reminded her that this wasn’t an obligation, this wasn’t work, not in the drudgery sense – it was tinkering. Most of the tinkering takes place outside, in the bright sun, in the sea air – what could be more pleasant?

I wrote the essay “Joy in the Task” two years ago for my writers’ critique group [The Room to Write, founded by Colleen Getty]. It seems fitting to share it here with a broader audience. I hope you find it of interest.

Sally M. Chetwynd

Brass Castle Arts

Email Me | Visit Website | Sign Up For Newsletter

To Tease Your Mind

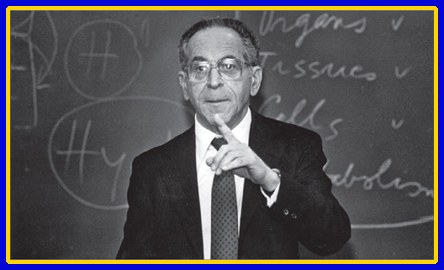

The greatest analgesic, soporific, stimulant, tranquilizer, narcotic,

and to some extent even antibiotic

– in short, the closest thing to a genuine panacea –

known to medical science is work.

Thomas Szasz

(1920-2012)

author, professor of psychiatry

Dr. Szasz’s most significant contribution to the practice of psychiatry was as the fulcrum on which the field changed its analytical direction. He proposed that “without a diagnosis of neurological disease or damage, a psychiatric diagnosis was meaningless. His work focused on the aggressive search for the underlying biochemical, genetic, and physiological bases of mental health disorders.” (The Lancet, October 20, 2012)

In a nutshell, Szasz recommends that first we eliminate all possible physical reasons for a mental disorder, before we chase after the origin of symptoms that are far less corporeal.

Today’s natterings have little to do with mental disorders, but the idea of work as something desired is more in line with mental health, what Szasz was really after.

Joy in the Task

In her gentle and often amusing memoir, “The Barn at the End of the World: The Apprenticeship of a Quaker, Buddhist Shepherd,” Mary Rose O’Reilley reflects on cultivation of a calm spirit and acceptance of work for its own sake. Too often we thrash at a task, all the sooner to get it over with. This preoccupation distracts us from seeing the joy inherent in our work.

She says, “A busy cycle of internal healing [deep, stage-four peace] operates while we’re unconscious [sleeping]. I’m convinced that the spirit, too, needs deep rest to reduce its habitual overdrive – rest that, in the mercy of creation, used to be woven into the daily fabric of chores. Vigils in the lambing barn, stacks of dishes to wash, a garden to weed – I smile to myself when I hear my children and young co-workers rail against this repetitive work. It takes half a life to realize that these unsung, secret, rhythmic occupations are creation’s gift to our species.”

O’Reilley also notes how Christian monks became depressed and lethargic after Vatican II mandated that Gregorian chant was unnecessary. The decline of their spirits without chant showed that this ritual serves as meditation, calming the soul to focus on the task at hand, simultaneously a prayer and a praise. Scottish women sang waulking songs when they spun wool; sailors sang hauling chanties when they raised anchors. Like Gregorian chant, the shared song brought pleasure and unity to the work.

It’s attitude. It’s a matter of a deliberate, mindful shift in how we view the task. And rather than considering it a task, which implies a burden, it is better regarded an opportunity, a stepping stone toward a goal, or yes, a gift.

Consider the accord of a farmer with his livestock. Milk the goat, trim the horse’s hoofs for shoeing, bed the chicken coop with clean straw, install a storm door in the bee hive before winter. It’s one-on-one. This mundane activity goes on, every day. But such intimate interactions build trust between the keeper and the kept, engendering well-being.

This applies to crops as well. The farmer tends his fields and orchards. Sow the seed, prune the apple tree, dress the field, graft the grapevine. Experience tells the farmer that careful stewardship yields a plentiful harvest and therefore generates patience (trust, related to faith) to wait for outcome of planting – weeks (lettuce), months (corn), or years (apples). This can be considered a symbiotic relationship. Yes, these occupations benefit the farmer, but they also promote the plants’ health and that of the soil.

Many activities – maybe most – we do because we must. With which attitude will we derive more joy in their doing, a positive one or a negative one?

Sometimes it’s a matter of acceptance of what is, without taking adversity personally, a vestige of a survival culture of older generations. On a recent weekend, Nelson, the man whose boat yard my family patronizes, took my mother and me in his little skiff out to our summer place on an off-shore island in mid-coast Maine. We unloaded our gear onto the beach and pushed his boat off for him to head back. Then his engine wouldn’t start. Rather than bemoan his plight, he took up his oars and calmly set about to row the three miles over open ocean to the harbor. Wiry and tough, the hands-on owner of a busy marina, he did what he had to.

Mother and I were uneasy with this prospect. When we climbed from the shore to the settlement, I went to a house where a number of neighbors were gathered, to ask someone to give Nelson a tow. Andrew immediately headed off. He caught up with Nelson at Indian Point, already half a mile along. Nelson was struggling against a brisk wind that was driving his high-sided boat onto the ledges. Andrew towed him to the mainland. With his signature, almost child-like wonderment, Nelson appreciated the assistance.

Nelson is representative of a generation that does what needs doing when it needs doing. It didn’t occur to him to ask for help. It’s probable that he would have made it back, because he always had, but still … he’s ninety years old!

In her book, “The Peninsula,” Louise Dickinson Rich notes the same unflappable grit in the hardy citizens of Corea, a tiny fishing village in Gouldsboro township away Down East. Independent and interdependent folks like this once peopled the tips of those rocky peninsulas that stretch far into the sea. Their remoteness from U.S. Route One and lack of tourist trappings insured geographical isolation until the late 1960s, which preserved their culture and economy.

The master boat-builder Alejandro (“Ale”) exhibits this philosophical nature in Daniel Gumbiner’s novel, “The Boatbuilder,” set in northern California. When Berg, the opioid-addicted main character, first comes on as Ale’s apprentice, he gets impatient at Ale’s instructions to sharpen the blade of a plane. The angle of the honed blade must be exact, so it will shave the wood, not gouge it. Every day for weeks, Berg hones and hones, never quite meeting Ale’s standard, never quite engaging his mind or heart. Then one day, it is correct, and Berg grasps a sense of patience it takes to truly learn one’s tools and one’s materials in order to learn one’s craft. That’s when he begins to apprehend how the creation – a wooden boat – growing under his hands endues him with its spirit, as his hands and heart build the spirit into it. Only then can Berg accept Ale’s gentle teaching to understand the transformation of a living tree into a living boat.

Early on, Ale asks Berg if he’s a punctual person. Berg affirms it, and Ale points out that Berg’s punctuality reveals his nature – he spends his mental energy anticipating the next thing on the docket, instead of investing himself in the task at hand, in the joy of the moment.

The work ethic, so often manifest with joy (whether or not realized), is intricately woven into our psyche. A strong work ethic necessitates the submission of one’s self-importance. The work ethic defined earlier generations. I’ve known many old men who learned their trades in their early teens, worked for decades, and died within a year of retirement. Set out to pasture, they had nothing to do; they knew nothing else. Their spirits withered because they no longer had the purpose that had sustained them for fifty, sixty, seventy years. Worse, younger generations were not encouraged to seek them out as mentors, so they could not even share their wisdom, to pass on what we call “tribal knowledge” today. Many occupations in which they found joy no longer exist, now obsolete in the wake of technology. Our throw-away society threw away these people.

Wendell Berry’s “The Art of the Commonplace” is a collection of meaty essays that shows the progression of our society’s headlong flight from ourselves, first by removing ourselves from the land (foolishly thinking we have no need for it), then the breakdown of the family structure, leading circuitously but ultimately (and presciently) to bankruptcy of the soul and the current denial of biology. Part of this includes denigration of menial work, resulting in a decline of the work ethic. He maintains that work need not equate to drudgery. He endorses a return to the land to reestablish the family structure, where elders lead by example to teach to the young the satisfying value of work.

Berry tells a marvelous little story about taking his granddaughter, age five, out in a horse-drawn cart one winter day to clear brush from a field on his farmland. They tend to the task, the little girl helping as guided, then head home in the growing dusk. On the way, she says nothing, and he becomes dismayed at her silence. He thinks perhaps she’s angry because she’s tired, cold, and bored silly. But then she pipes up with, “Grampa, didn’t we do good work today?”

Berry reminds me of a tough job taken on by the civil engineering company where I worked some years ago. The developer was building a road designed to culminate in a cul-de-sac, to serve three new houses set on islands of upland surrounded by wooded wetland. The road had been designed, in plan and profile, but no one realized until the road was built that a previous engineer had never finished the design of the cul-de-sac. There stood the developer, my company’s civil engineer, the town engineer, and the contractor, contemplating the torn-up mess of gravel and mud.

After studying the problem for several minutes, the town engineer asked the contractor if he could grade the cul-de-sac to spec, given the area’s limitations. If he could, then the engineers would survey the final construction for compliance and submit that as an as-built. As soon as it was agreed, the contractor turned to his son, a sturdy 13-year-old boy working for his father for the summer. The boy sat atop an industrial tractor, waiting for instructions. “Go do it, boy,” the contractor said, and the boy began. His precise operation of the tractor evinced confidence. He knew his tractor and he knew his job. At his father’s elbow, he was learning both a trade and pride in doing it well. He knew joy.

It isn’t hard to find joy even in the lowliest task. Some years ago, I worked part-time for my husband’s boss, whose firm cleans offices. My assigned facility had two large bathrooms with multiple stalls. My habit was to apply a swirl of bowl cleaner under the rim of each toilet first, giving the detergent time to coat the bowl. In a few minutes, I’d come back with the brush. One time, a perfectly symmetrical pattern formed in one of the toilet bowls, a starburst of dark-blue cleaner against the white of the bowl. I stood there gawking at the delicate elegance, reluctant to ruin it with the brush.

Yes, I know I’m weird. But that doesn’t negate the fact that beauty can be found anywhere, including a toilet bowl, if one’s mind and heart is open to it.

Speaking of plumbing, in his book “Excellence,” author John W. Gardner (founder of Common Cause, not the novelist) refers to this humility when he writes, “We must learn to honor excellence in every socially accepted human activity, however humble the activity, and to scorn shoddiness, however exalted the activity. An excellent plumber is infinitely more admirable than an incompetent philosopher. The society that scorns excellence in plumbing because plumbing is a humble activity and tolerates shoddiness in philosophy because it is an exalted activity will have neither good plumbing nor good philosophy. Neither its pipes nor its theories will hold water.”

If the job didn’t need doing, why would we bother with it? A humble attitude can bring much joy, when we remember that we are not above the task. The harder the work, the greater the joy in conducting it. The greater its challenge, the more satisfaction we derive in meeting it. The satisfaction is as much in the effort as in the result. We don’t always meet the challenge, but therein lies a valuable “take-away,” too. Failure teaches us more than does success, so it behooves us to appreciate it.

In Gordon Bok’s folk song, “Old Fat Boat,” the protagonist declares contentment with his situation. Although he lives on a slow, old boat that’s “soft in the transom” (needing repair), has “a two-pound splinter” in his thumb, and has run out of tobacco and cheese, he’s snug in his cabin against the wind and rain outside, with a bit of homemade bread (old but nice), coffee, tea, tuna fish, beans, and toddy.

Well, mercy, mercy, I do declare,

If half the fun of going is a-getting there,

Mercy, Percy, you better start rowing,

‘Cause the other half of getting there is going.

Look for the joy in the other half. It’s there.

Updates on My Own Writing Projects

I often mention the writing of friends and associates here, but rarely talk about my own stuff. So here goes!

Last Christmas Day, I began work on what I intended as a short story. But with a word count already exceeding 20,000 words (and the story arc still isn’t complete), it has taken on the proportions of a novella. It’s about Nicodemus, one of the few Pharisees brave enough or open-minded enough to ask sincere questions of Jesus of Nazareth, not to dismiss him as another zealous crack-pot.

I’ve wondered for many years about Nicodemus. We don’t know much about him because he shows up only three times in the Bible, all in the book of John. Did he come to believe that Jesus was the Messiah? We’ll never know for sure, but his actions in those few mentions point toward that inclination. We know the Jesus story, but we don’t know the Nicodemus story. The Bible is not about Nicodemus, after all. It’s not a matter of omission; other than those few places, he’s not relevant to the story.

Nicodemus has poked at me quite often over the years, making me wonder: Well, what was Nicodemus’s “take” on the whole Jesus phenomenon? So, this is my current writing focus. I think it’s a secular story, but I can’t say I’m sure of that. I am having loads of fun digging into Biblical-era Jewish culture, domestics, economics, and politics, as well as the tenuous relationship between the Jews and the occupying Romans. This helps to develop the person of Nicodemus as a man of his times.

Who knows when I’ll get it done – I always maintain that a story takes as long as it takes and is not governed by arbitrary limitations or rules – but the ride is a hoot!

Calendar & Announcements

Sept. 11, 2021 – Saturday – Wakefield Farmers Market

Hall Park, 468 North Avenue, Wakefield, MA

9am – 1 pm

I’ll be there with my books and those of several fellow authors. Come on by!

Sept. 11, 2021 – Saturday – Merrimac Mic Open Mic event

Merrimac Public Library, 86 West Main St., Merrimac, MA

6 pm – in person and via Zoom

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/8075677136?pwd=Snhackpxd1lFMHhaZjB3ZjZuZFFMUT09

Meeting ID: 807 567 7136

Passcode: 0WT0RR

Bring your own writing to share – poetry or prose – for a few minutes at the mic. As host Isabell Van Merlin always says, “All the best words!”

Sept. 25, 2021 – Saturday – Colonial Faire & Fife & Drum Muster

Longfellow’s Wayside Inn, 72 Wayside Inn Rd. (just off Rte 20), Sudbury, MA

10 am – 4 pm

Admission: $3 – Free parking – Family-Friendly

Loads of local artisans and craftspeople! Start your Christmas shopping!

Live fife and drum music all day!

My corps, The Musick of Prescott’s Battalion, will be performing.

Oct. 2, 2021 – Saturday – Wakefield Festival By The Lake

Arts & Crafts on the Lower Common, Wakefield, MA

10 am – 4 pm

Get even more Christmas shopping done!

(rain date – Sunday, Oct. 3, 2021)

Oct. 9, 2021 – Saturday – Wakefield Farmers Market

Hall Park, 468 North Avenue, Wakefield, MA

9am – 1 pm

I’ll be there with my books and those of several fellow authors. Come on by!

Oct. 16, 2021 – Saturday – Boston Book Festival

Copley Square, Boston, MA

10 am – 4 pm

Literary vendors of every ilk, books to buy, seminars to attend.

Look for me in the ARIA booth this year (Assoc. of Rhode Island Authors).

Dec. 11, 2021 – Saturday – ARIA Book Expo

Rhodes on the Pawtuxet, 60 Rhodes Place, Cranston RI

10 am – 4:30 pm

100+ authors – including yours truly – exhibiting books of every genre.

Panels and seminars on writing and publishing; raffles; free admission.

Another chance to fill those holiday gift needs.

Conversations

Do you have comments or questions about this post?

I’d love to hear them. Let’s talk!

Happy reading! Happy writing!

Sources

Image: door lock assembly

https://www.obo-7.xyz/ProductDetail.aspx?iid=55516319&pr=28.99

Image: Thomas Szasz

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61789-9/fulltext

Image: painting – man rowing dory

N. C. Wyeth, Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine

https://www.portlandmuseum.org/wyeth

Image: woodworking plane

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plane_(tool)

Image: leaking pipe joints

https://mikediamondservices.com/blog/4-plumbing-quick-fixes-learn/

Image: Nicodemus

https://angelusnews.com/faith/saint-of-the-day/saint-of-the-day-nicodemus/