Monday, December 21, 2020

The Great Relocation

Quite a few of you out there in NewsletterLand have undoubtedly been busy relocating snow in the past few days. So have I. We all have snow tales to tell, some of them tall (some of them far taller than the mounds of relocated snow), some of them small.

Snow is an evergreen (er, everwhite?) subject. Some winters go down in history for record snowfalls, like 2011 and 2015 here in New England. Others are quickly forgotten for the lack of record snowfalls, like last winter, when eastern Massachusetts received less than a foot total. Last winter’s snowfall worked out just fine for me. We had two or three small deposits in December and January. In early February I broke my arm, rendering me useless with a shovel. But we had no more shovel-worthy snow – a dusting here, an inch there – no more.

After the snow stopped the other day, I ventured out to tackle the Great Relocation, armed with my trusty shovel. Because I’m working from home this winter, I can pace myself. Usually I have to do the whole thing in the dark after work, or long before dawn to get out to go to work – again, in the dark. Sometimes my neighbors aren’t around to help.

This time, three neighbors provided major mechanical assistance – two with snow blowers did the sidewalk and one with a plow pushed the pile at the end of the driveway to either side. So I cleared one side of the front steps, the back steps, and the walkway up the side of the house to access the trash barrel, which had to go out that night. I also cleared a section through the ridge along the street to make a place for the trash barrel. Enough to get a car out. Enough to let food delivery in, which we did for supper.

our house

The next day I cleaned off the cars and finished the driveway. The third day I opened up the other side of the front steps and the path to the driveway. This area often serves as snow storage when the winter really dumps on us. Our yard is miniscule and surrounded by fence, so there’s not much room to put the stuff.

This storm left us with well over a foot – about fifteen inches. Someone quipped on the radio that Boston received more snow in this one storm than it did all of last winter. True. It remained cold – a steady 24 degrees F – so the snow remained fine and dry, which I like. The wind packed it, which I also like, because it stays in one piece and sails gracefully off the end of the shovel where I direct it. Ideal shoveling snow, in my book.

The good news is that my bum arm is doing fine. Both arms and wrists were a bit achy, along with my shoulders, my lower back, and … The spread-out exercise kept them all limber. A mug of hot cocoa, with my feet up in the comfy chair, made for a fine reward.

Speaking of rewards, I do not neglect my helpful neighbors. They get a loaf of my oatmeal bread every time they relocate snow for me. I’ve found a distinct relationship between the depth of the snow and the number of loaves I need for collateral. Up to six inches: I can do it all myself easily and quickly. Six to twelve inches: one loaf is usually adequate. Twelve to twenty-four inches: two loaves are required. Over twenty-four inches: a minimum of three loaves keeps the neighbors happy.

my oatmeal bread fresh from the oven

Sally M. Chetwynd

Brass Castle Arts

Email Me | Visit Website | Sign Up For Newsletter

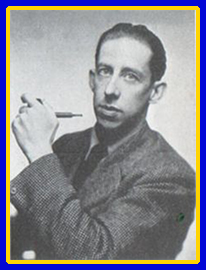

To Tease Your Mind

Surely of all things in the world,

the rarest is a civilized man at peace with himself.

Jean-Pierre Gontran de Montaigne

Vicomte de Poncins

a/k/a Gontran de Poncins

(August 19, 1900 – September 1, 1962)

adventure writer and amateur anthropologist

of minor French nobility

As a young adult, Poncins grew interested in human psychology, “searching, he said, for what it is that helps people make their way through life” [quote from Wikipedia]. The businesses toward which his heritage directed him bored him, so he took a different path. He became a freelance journalist and sold accounts of his travels to periodicals. His primary passion was for small populations culturally intact and unsullied by modern civilization. The extremes of his journeys in the 1920s and 1930s took him to Tahiti and the Canadian Arctic.

He later served with an American paratrooper unit in World War II; was drawn to China to study remote habitats there; and lived in a Chinese enclave outside of Saigon in South Vietnam that had retained its ancient cultural heritage. Besides the work published in periodicals, he wrote five books – Kabloona, From a Chinese City, Arctic Christmas, eskimos [sic], and The Ghost Voyage Out of Eskimo Land.

Poncins found that despite the extremes of the Eskimos’ environment, close to the North Pole, a place with the most inhospitable conditions in the world, they were a people at peace with themselves. Thus, the quote above.

Natterings & Noodlings: Snow and Cold

As children, my brothers and I eagerly listened to the radio on snowy mornings to learn if school was canceled. If so, we had a glorious day to romp in the cold. Our cold-weather clothes were just like Ralphie’s and Randy’s winter gear in the neo-classic film, “A Christmas Story.” It was hard to get up when we fell down, swaddled in heavy woolen coats and bulky snow-pants. No doubt we looked like slugs, too.

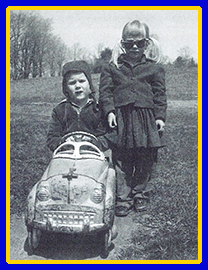

April 1958, and I still have my snow-pants on for outside play.

(This is my brother Duffy’s and my Bonnie & Clyde impression.

What a grim pair.)

I don’t remember helping to shovel snow as a child, but my brothers and I must have done so. My father didn’t have a snow blower, so the Great Relocation was all done by hand. No sooner was the work done than play began. The mountains at the corners, where the driveway met the road, were ideal for snow forts – well packed and dense. We carved out parapets and banquettes, stockpiled snowballs, and lobbed our ammunition at each other across the driveway.

My brother Duffy, next older to me, has always been a builder. Maybe he got his start as a child in South Berwick, Maine. In the summer, he constructed small huts from the tall field grass woven into frames made of goldenrod stems. One winter, he made a five-room igloo, diligently guaranteeing its long life by dousing it with buckets of water, hauled from the house after dark, to freeze solid overnight. Come spring, the igloo was a long time melting.

My oldest brother Bill didn’t play much with the rest of us, being far more interested in glass vacuum tubes, circuits, and ham radio sets (“K1PLS – K1 Peter Loves Sugar”), but now and then he’d be outside with us in the snow. He couldn’t be bothered with mittens. They got in his way, he said, as he formed snowballs and snowmen with his bare hands. I’ve seen him in later years, going about in the cold weather in little more than a heavy shirt while the rest of us are smothered in wool.

We moved to Madbury, NH, in 1964, twelve miles from our Maine home. The climate wasn’t any different. We were still in the country, still within spitting distance of tidal waters, still surrounded by open fields edged with woodland. This house is a three-story farmhouse with attached sheds culminating in a large barn.

In the late 1960s, we had a storm that left a monstrous drift in front of the barn, its crest above its eaves. Duffy and Doug, a buddy who had stayed overnight, climbed up that drift to the roof. Doug had a new winter coat, made of a synthetic fabric – new-fangled polyester. It was shiny and smooth. On a whim, Doug dropped to his belly and rode that slippery coat down the drift, his momentum carrying him to the middle of the hay field. Our woolens never would slide like that. Then we dug a hole in the drift big enough for our full-sized circa-1963 Dodge van, parked in the barn, to drive through. After that fun, we knocked it down and cleared it away.

my mother in our Dodge van in front of our barn

Maine has a history of “big” winters, typical of northern regions. I lived Down East in Washington County in the late 1970s, and some of those winters met the “big” criteria. The Great Blizzard of 1978, which my husband and most others in Massachusetts still talk about, dumped so much snow on that state in three days that nobody could go anywhere for a couple of weeks. I don’t remember that particular blizzard, because where I was, in East Machias, it began to snow one day and didn’t stop. For weeks. After four days of waiting it out, it dawned on everyone that this storm wasn’t going to be “waited out.” So we all set to with our shovels and went about our business, the flying snow be damned. Yes, every day as we came and went, we had to shovel our way out and shovel our back in again, but what else could we do? We didn’t have the body-fat reserves of hibernating bears.

A snowstorm blew in on Christmas Eve the next winter, dumping a couple of feet of the stuff. I headed further Down East to Perry, a coastal town opposite Canada on the St. Croix River, to celebrate the holiday with my sister-in-law and oldest nephew. I drove a tough old Saab station wagon. Approaching their driveway, I built up a head of steam and blasted through the pile the plows had left, to get off the road. Sleeping bag and Christmas presents under my arms, I waded through the storm to the house.

It came off 40 below zero for the next three days. A neighbor’s house caught fire on Christmas morning, leaving a young family of four in their nightshirts out in the cold. We all grabbed something to take to this family. We walked, rather than shovel out the cars: time was of the essence. I took a favorite old sweater my mother had found at a rummage sale and had mended its many moth holes. It was knee-length and warm. (Twenty years later, my sister-in-law returned the sweater to me – the neighbor remembered where it had come from!)

After three days of this unreasonable cold, my sister-in-law announced that we had to go get groceries and water (her house didn’t have a well) and do laundry. My car was the last one in, so it had to be the first one out. We cleared away around both cars and got into mine. I put the key into the ignition and turned it. The three of us listened, breaths held, to hear if it would turn over. Nothing for a long instant. Then, a barely audible, gravelly groan. I turned the key again. Another faint growl. The third time, the engine roared to life! That was a Sears DieHard battery, and it wasn’t young. I was impressed!

these 4-cylinder Saabs were tough little cars

(mine was a blue 1972 Saab 95 station-wagon model)

Phillip and I lived in downtown Portland, Maine, from 1990 to 1996. Because the driveway between the buildings was very narrow and the small lot that served the three apartment houses was too crowded to turn around our van, Phillip had to back in every night when he came home from his second-shift job. During our winters there, I got in the habit of setting the alarm for 1 am. I’d get up, buckle on my shovel holster, go shovel the OK Driveway, come back in and drop into bed, barely waking up. Most nights, only the edge of the street needed it. But it had to be done: even with weight over the rear axle, a van has practically non-existent traction, and Phillip didn’t need the worry that he’d slide into the brick house on either side.

Our last winter there, the new landlord didn’t remove the snow the way the old landlord had. He had it plowed instead. This meant that the longer the winter went, the smaller the parking lot became. Our kitchen windows looked out over another driveway, broad and wide, that served the house on the corner. The plowed snow piled higher and higher. We were on the first floor, which stood five or six feet above the ground. The snow pile eventually blocked our windows, topping out at twelve feet high. It was disconcerting to look out while eating breakfast and see, above my eye level, the neighbor’s dog four feet away doing a dump on top of the pile. Come spring, an added bonus was the stink of doggy-doo coming through the open windows. That snow didn’t melt until June.

Here in the Boston area, we are all too familiar with the winters of 2011 and 2015, both remarkable in that the record amounts of snowfall each fell within one month. In 2011, the big storms began the day after Christmas and occurred every Monday and Thursday until the end of January. For most of us, our daily routine was eat, sleep, and shovel, and squeeze in time to go to work. One could set the clock by the storms’ regularity.

(somebody was creative in 2015)

Then 2015 blew in. The snow slammed us from January 26 until the first week of March, creating a new Boston record with 108 inches. Tuesdays and Saturdays were the storms’ favorite days to strike. I was working in Boston and taking a class in copyediting at Emerson College. I managed to attend all 13 classes, but the first four were postponed because of snow. On class days, I rode the shuttle from work in Allston to downtown Boston. The shuttle drivers had to navigate snow-clogged streets, now barely one lane wide, cars so deeply buried in snow on either side that they wouldn’t see the light of day for weeks, white mounds the only evidence of their presence. People laid bets on when the snow in the city’s snow-storage yards would disappear, mountains a hundred feet high, the tractors working them looking like toys. The last of that snow trickled away in mid-July.

slush wave on Nantucket Island, February 2015

almost frozen in place

On March 10, 2015, I received an email from a fellow writer in Connecticut, who noted “I hear they are spreading black sand on Fenway Park in an effort to melt several feet of snow.” Clearly we had more than enough snow that year. Red Sox Opening Day was on April 6, less than a month away.

I’m sure hoping that this early storm isn’t a harbinger of the winter to come.

A Book Worth Checking Out

Kabloona (1941)

Kabloona (1941)

Gontran de Poncins

We can talk up a storm on the subject of winter, snowfalls, and cold, but our tales don’t hold a candle to those of Gontran de Poncins who, in his book Kabloona, relates his adventures living above the Arctic Circle with the Inuit. He has bragging rights.

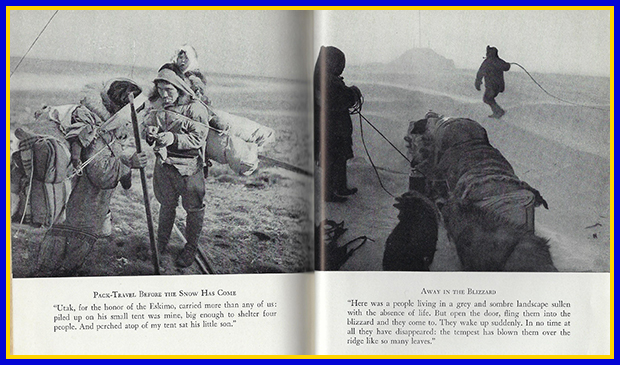

Kabloona was compiled from notes that Poncins took during the fifteen months (1938-1939) that he lived with Inuit peoples in far-northern Canada, near the North Pole. He joined them in the hunt for seals, built igloos with a machete-like snow knife, ate raw seal meat slashed from frozen carcasses brought into the igloo for the night to keep predators from them, cared for the dogs that provided essential transportation and draft services – every activity that made life above the Arctic Circle possible.

Collaborating with Poncins, an editor at Time-Life Books compiled and organized Poncins’ notes and published Kabloona in 1941 as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. It was a huge hit with American readers and is considered a classic in travel literature (although I doubt it enticed many readers to follow suit). Poncins’ own illustrations (he studied art as a youth) and photographs add considerable depth to the story.

Among Poncins’ observations that I remember in particular is about the transformation by the advent of snow. It’s fall when he arrives at a Hudson Bay trading post to await winter and his Inuk guide to remote villages whose natives have never seen a white man. The Inuit who have come to trade for goods before heading back north for the winter look slovenly and shiftless. Their dogs lie in the muddy street and burrow under the raised boardwalks, uninspired to make the least effort unless it involves a scrap of food.

photographs by Poncins from Kabloona

Then a snowflake drifts down from the sky. The dogs immediately emerge from their burrows and stand alert, looking up, sniffing the air. They quiver with anticipation. As more snow falls, they cavort and dash about, barking and howling. When the natives’ sleds are laden, ready for the trip home, the dogs leap to their places, eager for their traces, and can barely stand still long enough to be harnessed. The assemblage doesn’t resemble the inert creatures that previously slouched around. They take off toward the north like a rocket – each a single unit of a man and his family, his goods and sled, and his dogs, focused on the northern white horizon blurred by the driving snow.

We don’t see this exquisite joy much in our own comfortable, relatively unchallenged lives. We assume that the day’s work, for Eskimo or dog, is demeaning drudgery. At best, we would find it so; at worst, cruel torture. But these aborigines of the Arctic are born to this and for this, and the snow makes them alive. And their joy is in the acceptance of its pure simplicity.

Word’s Worth

kabloona origin – Inuit; a term initially used to mean anyone not of Inuit blood, later a white person. In Kabloona, Poncins uses it as his native friends do, poking gentle fun at a white fellow entering their land whom they consider a greenhorn, an inexperienced tenderfoot. The word comes from the Inuktitut quallunaaq or the Inuinnaqtun qablunaaq, for qalluit (“big eyebrow”) – the bushy eyebrows that the Inuit saw as a distinctive feature of whites.

Inuit This is the name that these people call themselves, meaning “The People,” collectively including many, but not all, of the aboriginal tribes who inhabit the extreme northern latitudes around the North Pole. A single person of the Inuit is called an Inuk.

Eskimo The term “Eskimo” has been applied for centuries by outsiders generically to Arctic peoples. Sometimes it has been considered derogatory, although recent etymological research suggests that it derives from the French word esquimau, meaning “one who nets snowshoes,” the weaver of sinew into a net that is fixed in a flat frame, resulting in a snowshoe. Other research traces it possibly to Algonquian, Micmac, and Ojibwe languages. Some Arctic Native American tribes refer to themselves as Eskimos; some of these peoples are of Inuit lineage and some are not.

Trivia

In Kabloona, Poncins notes how the Inuit waste nothing. They collect their dogs’ turds and use them to grease the runners of their sleds, to prevent ice from building up.

Conversations

Do you have comments or questions about this post? Let’s talk!

Happy reading! Happy writing!

Sources

Image: Gontran de Poncins

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gontran_de_Poncins

Images: Kabloona book cover

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabloona

Black-&-white photographs scanned from book

Definition of kabloona

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/kabloona

Inuit and Eskimo

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/04/24/475129558/why-you-probably-shouldnt-say-eskimo

Image: frozen slush wave on Nantucket Island, February 2015

photograph by Jonathan Nimerfroh

https://boston.cbslocal.com/2015/02/26/nearly-frozen-waves-captured-on-camera-by-nantucket-photographer/

Image: snow dragon eating car

https://www.reddit.com/r/photoshopbattles/comments/2n7fcc/psbattle_snow_monster_eating_car/

Image: Saab 95

http://momentcar.com/saab/1972/saab-95/